We continue to wend our way through Northern Europe, moving south from Estonia into Latvia to explore its capital city, Riga.

Despite its close proximity to Estonia, the people of Latvia belong to a different ethnic group, the Balts. In antiquity there were roughly eleven Baltic tribes, who survived as farmers and amber gatherers; today it is only the descendants of the Latvian and Lithuanian tribes that still exist. While ethnically different, their modern history reads very much like that of their northern neighbour (you can read our Estonia report here).

At the turn of the 13th century the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, which would ultimately be absorbed by the Teutonic Order, were hard at work coercing the Latvian pagans onto the path to salvation. In 1201, the Livonians founded the city of Riga, although a settlement had existed here on the banks of the Daugava River as far back as the 2nd century. With the Germans now in control of the city’s administration it prospered, and by 1282 was a crucial trading port within the Hanseatic League. Beginning in the 16th century, the Teutonic Order was struggling to contain the ambitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, and the Russian Empire with the result that Latvia was very quickly shared between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden. Russia however would not be denied, swallowing Latvia and the rest of the Baltic region during The Great Northern War (1700-1721). Latvia did well as part of that Empire, Riga in particular. Before too long the number of native Latvians living and working in Riga surpassed that of German residents although German would continue to be the official language until 1891 when Russian took its place.

As the Latvians became better educated their desire for a national identity gained strength. The Latvian National Awakening began in 1868 with the establishment of the Riga Latvian Association. The first national song festival followed in 1873. As the 20th century dawned, the number of industrial workers in Riga was eclipsed by only that of Moscow and St. Petersburg. The 1905 revolution that began with workers in St. Petersburg, was quickly embraced by factory workers in Riga and soon spread to rural communities – with the difference that the disaffected in Latvia were more angry with the German feudal system still in place than with the Russian tsar. The revolution was suppressed with a significant human toll. When Germany declared war on Russia in 1914, the Latvians sided with Russia suffering mightily in terms of lives lost and property damaged but emerging from WWI with a renewed yearning for a nation of their own. The Latvian War of Independence began on December 5, 1918, and lasted for nearly two years before the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic was formally recognized by both Russia and Germany. World War Two did not favour Latvia. In 1940 the Red Army invaded and while the Germans would do their best to force the Russians to retreat, they would fail. The Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic would remain part of the USSR until August 21, 1991 when it was officially recognized as an independent nation, the Republic of Latvia.

Dollars – Our all-inclusive nomadic expenses for 7 nights in Riga averaged out to $157/day Canadian ($115 USD / €109). Basic day-to-day living expenses (hotel, food, activities, local transportation) were only $109/day Canadian ($80 USD / €76) – everything seems to get less expensive as we move further south into Europe.

Environment – We stayed in an Airbnb about five blocks from Riga’s old quarter. Comfortable enough and well located, but we both realized we do not like basement suites – the inability to see outside is depressing.

Tips, Tricks & Transportation – Riga is roughly a 4.5-hour bus ride from Tallinn. Several companies operate the route and we chose Lux Express. It was a good choice with comfortable seating, complimentary water bottles, in-seat entertainment systems, free wifi, and only €16/pp ($23 CAD).

Out and About – The streets of Riga were made for walking, and every day we found something new to delight our visual senses.

Beginning in 1890 and continuing for the next 20-odd years, a new architectural aesthetic exploded across Europe. Known as Art Nouveau, the highest concentration of this type of architecture in Europe can be found in Riga, with one-third of its buildings stunning examples.

The highly ornate and colourful style is characterized by arches, curving lines, and vertical composition, alongside stylized plants, animals, insects, and flowers.

Alberta iela and Elizabetes iela are two of the best streets to wander along and appreciate these works of art.

The Vecrīga (Old Riga) neighbourhood is the historical center of the city, full of pieces of the past. These are a few of our favourites:

At more than 70,000 square meters (750,000 sq ft), the Central Market is one of the largest markets in Europe. In the 1920s, five zeppelin hangars that had been abandoned during WWI by the German army in Kurzeme (about 12 km/7.5 miles northwest of Riga) were relocated to the city center.

More than 3000 vendors fill the hangars (each about the size of a football field) with each hangar dedicated to a particular product (fish, meat, dairy, vegetables, and gastronomy), interspersed with stalls selling Latvian-made souvenirs.

In the mid-15th century the Brotherhood of the Blackheads, a guild for unmarried merchants and shipowners, took possession of the biggest public building in Riga, revamping the old warehouse into the House of the Blackheads, the original frat house. In keeping with its social nature, in 1510 the City’s first decorated Christmas tree was placed in the plaza out front. World War II bombing damaged much of the structure but the original blueprints survived and an exact replica of this feast for the eyes was completed in 2001, Riga’s 800th birthday.

Believed to have been built by members of the same family over the course of several generations, the Three Brothers reflect the changing architectural styles in the city. The oldest house, dating from the 15th century, is a Dutch/Gothic design and is the oldest stone residential building in Riga. The middle brother is a 17th-century Renaissance structure painted a pleasing pale yellow, and the baby of the family, the thinnest of the houses, was built in the 18th century. Its green paint colour was apparently to ward off evil spirits.

Very little remains of the defensive walls that once surrounded Old Riga. Of the eight gates that granted entry to the city in the 17th century, only the Swedish Gate still stands. Urban legend says the gate, which led directly to the Swedish soldiers’ barracks behind, was a clandestine spot for local girls to meet their Swedish lovers, a verboten relationship. On one particular evening when a soldier failed to appear at the appointed time, the townsfolk grabbed the young lady waiting and as punishment entombed her in the walls of the gate. In the darkness of night, if your love is pure, you can still hear her declarations of love. The picturesque gate is a popular spot for wedding photos.

Near the Swedish gate, and part of the same wall foundation (which actually dates from the 14th century), is the last surviving watch tower (there were originally 18 such towers). Gunpowder was stored behind the thick walls of the Powder Tower and several cannonballs from bygone battles are visible in the brick walls.

Medieval guilds held a monopoly on their respective trades, making membership imperative for anyone who wanted to legally operate a business. Founded in the 13th century, the Great Guild in Riga welcomed affluent German merchants into their ranks, while membership in the Small Guild was open to German craftsmen and shopkeepers.

This type of discrimination continued for centuries, before, supposedly, it came to a head. In 1909, a wealthy Latvian businessman who had been continuously rebuffed in his efforts to join the Great Guild constructed a grand office building (now known as the Cat House) across from the Guild. At each corner of his rooftop, pointing directly at the Grand Guild, he placed cat statues presenting their backside, tails in the air. A lengthy court battle ensued, with the end result that the Latvian tradesman was allowed to join the Guild and the cats were re-positioned.

Churches are around nearly every corner of the Old Quarter, each unique and attractive. Virtually nothing remains of the original St. Peter’s Church save for sections of the 13th-century walls. Over the centuries it was remodeled and rebuilt before suffering massive damage from German bombing in 1941. Despite the Soviet Union’s unofficial policy of atheism, restoring the state-owned building to its former glory began in 1967 and was completed in 1983, although Lutheran services would not be held again until 1991 after the Soviet Union crumbled.

The largest place of worship in the Baltics is another 13th-century church, the Riga Cathedral. In keeping with its impressive size, in 1882/83, while it was undergoing restoration work, the largest pipe organ in the world (6768 pipes) was installed. During Soviet occupation, the cathedral was used as a concert hall and today its organ is only the fourth largest in the world.

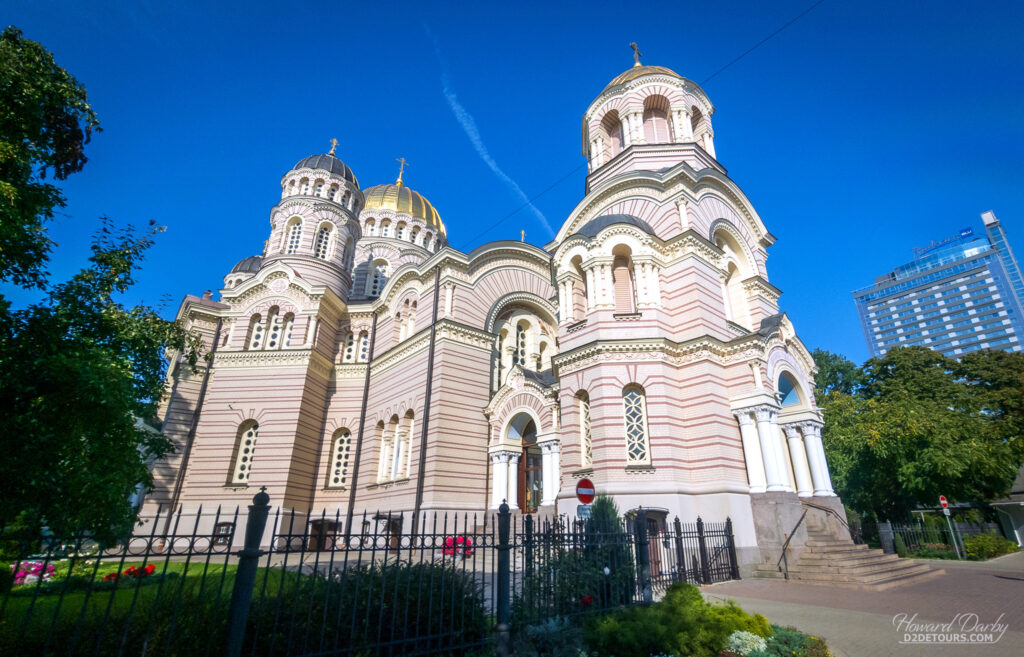

During the Russification of Latvia in the latter part of the 19th century, the Orthodox Nativity of Christ Cathedral was constructed. A complete contrast in both colour and style to the Lutheran churches found elsewhere in Riga it too served a different purpose while Latvia was part of the USSR, functioning as a planetarium and scientific lecture hall.

The Freedom Monument unveiled in 1935, replaced a statue of Peter the Great. It is a memorial to the soldiers who died during the Latvian War of Independence (1918-1920) and stands as a testament to their fierce national pride. Interestingly, it was not demolished by the Soviets who occupied the country just a few short decades later. The changing of the guard ceremony takes place every hour between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m., although inclement weather and public festivities can affect that schedule.

Erected in 1970, the Latvian Riflemen Monument is one of the few remaining ideological sculptures in Riga. As a unit of the Russian army, the Riflemen were formed in 1915 to defend the Russian Empire (of which Latvia was a part) from Germany. Radicalized by the Bolsheviks many became staunch supporters of Lenin during the 1917 Revolution, while others returned to their Latvian homeland. The memorial is viewed with mixed emotions. Some see it as honouring Latvian military heroes, while for others it is simply a reminder of Soviet occupation.

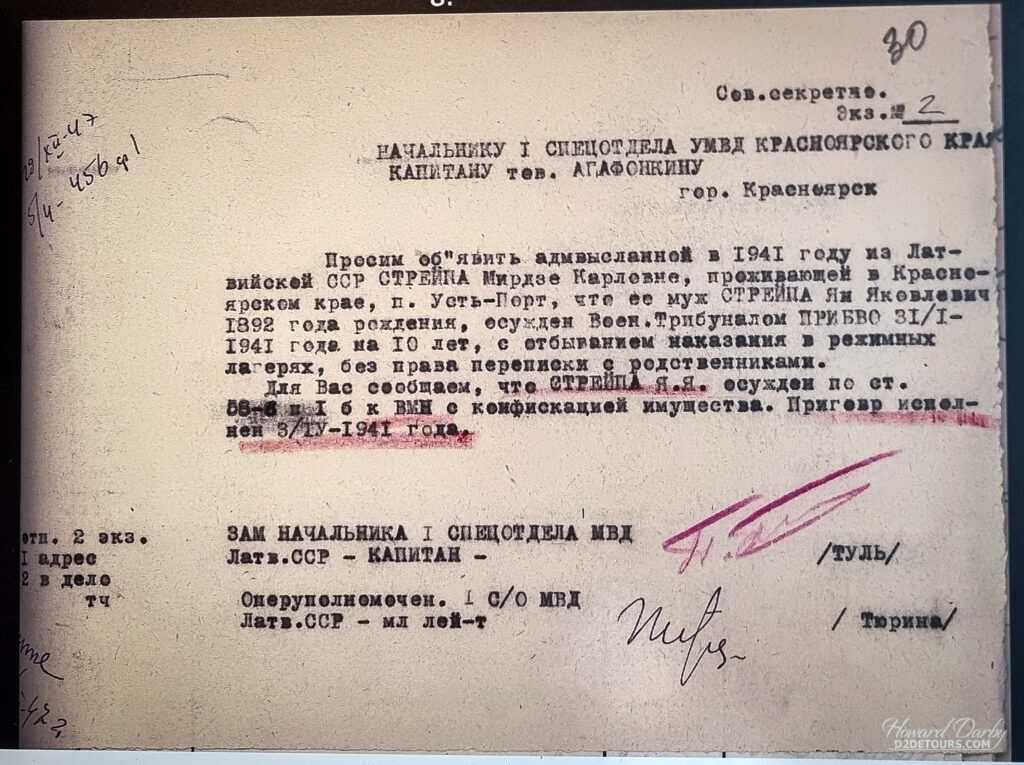

On June 17, 1940, Soviet troops invaded Latvia and what followed were decades of anguish for the Latvian people. The Art Nouveau building that once housed a music school, bookstore, flower shops, and a pharmacy would become a symbol of terror – The Corner House.

Once you were summoned and entered through the non-descript wooden door you were in the hands of the Cheka (KGB). Today it is a museum with the main floor dedicated to the grim stories of those whose lives were forever changed, told through the documents found in the building. The lower level contains cells and interrogation rooms. Guided tours (€10/pp) of the lower level may be booked online (and sell out quickly) but we opted to only view the main floor which is free, and honestly was sobering enough.

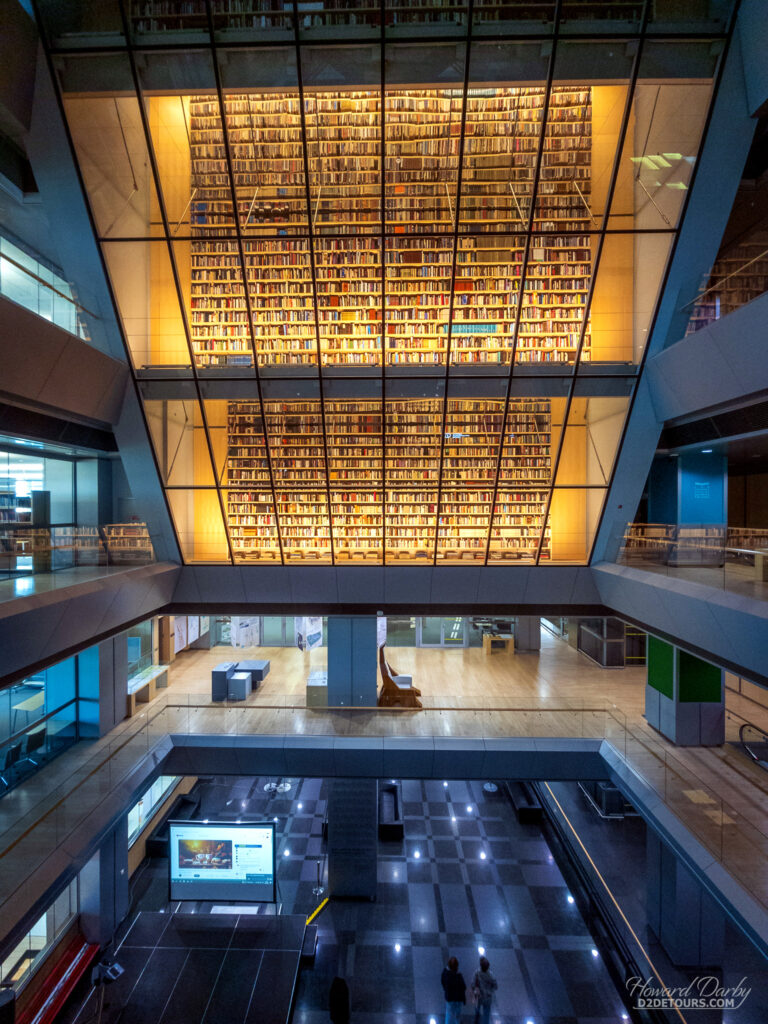

Across the Daugave River from the Old Quarter is the National Library of Latvia, built in 2014. Nicknamed the Castle of Light, its design was inspired by the Latvian legend of a castle, the symbol of culture and knowledge, lost to the murky depths of the river as the country is ravaged and overrun. As the Latvian people clawed their way out of the resulting despair so too did the castle ultimately re-emerge from the darkness. The 11th and 12th floors of the library are housed in a glass flame and afford one a panoramic view of Riga.

Us – Much like the people in Tallinn, Estonia, the residents of Riga are not openly friendly. I wondered whether this might stem from so many decades of Russian oppression during which people learned to mask their emotions out of fear that some expression might be misinterpreted and lead to trouble. Despite the reticent nature of its inhabitants, the city does have a lively and inviting feel to it; we enjoyed every minute spent strolling its streets. Off to Vilnius, Lithuania!

Restaurants – We have to admit failure in the Latvian food department. We did try some chicken, mushroom, and cheese pelmeņi (dumplings), which were delicious slathered in sour cream, but we neglected to take a picture. The enormous brownies (a traditional chocolate version and a cheesecake one) were scrumptious each time we stopped by the bakery near our Airbnb, but again we forgot to memorialize the yumminess – possibly because we ate them too fast!

Speech – You will likely hear three languages in Riga: Latvian, Russian, and English. Latvian is the only official language but nearly a third of the population is also fluent in Russian, a holdover from Soviet occupation when it was mandatory for every Latvian to learn Russian. Today, English is the foreign language of choice for young Latvians to learn, and is a requirement for anyone who works in the tourist industry.

- Labrit (luh-BREET) – Good morning;

- Labdien (luhb-DYEHN) – Good day;

- Labvalar (luhd-VUH-kuhr) – Good evening;

- Atā. (UH-tahh) – Goodbye;

- Jā (yah) – Yes;

- Nē (neh) – No;

- Lūdzu (LOO-dzoo) – Please (you might also hear this for you’re welcome);

- Paldies (pahl-dee-yes) – Thank you;

- Ai tu runā angliski? (vah-yee too roonaa angliski?) – Do you speak English;

- Piedodiet (pyeh-DOH-dyeht) – Sorry.

Your verbal and photographic tour of Riga is glorious. I am tickled by the Cat House story and enthralled by the stunning architecture.