After spending a month in Southern France, we still had time to fill before heading back to North America for Christmas. Weather-wise Tunisia is still very pleasant in mid-November (22°C / 72°F) and just a short hop from Nice.

Various explanations exist for the origin of the name Tunis, the capital of Tunisia (established in 698 CE). It may have been in homage to the Carthaginian goddess Tanith, or might have evolved from a Berber word for “pass the night” – perhaps referencing the last stop on the overland route to the coast. Until the 19th century, it was the collective term for the country. Tunisia is a derivative of Tunis, and the French are responsible for that term entering our lexicon. Today one-fifth of the country’s 12.3M population lives in the metropolitan region of Grand Tunis.

The median age on the African continent is 19.2 years, yet in Tunisia it is 32.5 years. That discrepancy is largely attributable to the government’s family planning program which has reduced population growth to just over 1% per annum, and is key to the country’s economic and social stability. Though Islam is the state religion, Tunisia’s constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and it is an extremely tolerant Arab state. It actively participates in international affairs as a member of the UN, the Arab League, the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, and the African Union, among others, and maintains close economic and political ties with France and Italy. It is also a non-NATO ally of the US.

As part of the Byzantine Empire (after the fall of Rome), Tunisia was wholly Christianized. That changed with the Arab Conquest in the late 7th century when it became a mecca of Islamic learning, culture, and trade. Various Arabic dynasties ruled the region until the 16th century when Turkish Muslims felt they were better suited to rule. Under the Ottomans, Tunisia enjoyed a significant amount of autonomy, which may or may not have been a good thing. In the late 19th century, on the brink of bankruptcy and in the face of a collapsing Ottoman Empire, the nation was ripe for “rescue.” Over the strenuous objections of Italy, Tunisia became a French protectorate in 1881.

Without a doubt the French modernized the country, albeit in exchange for exploiting its resources. By 1956, Tunisia had had enough of external oversight and peacefully negotiated its independence. Although their first president was somewhat authoritarian, his policies were progressive, including universal education, women’s rights, and secularism. He was overthrown in 1987. In late 2010, beginning in Tunisia, a series of anti-government protests spread across much of the Arab world. Leaders were deposed, civil wars erupted, and general chaos reigned (and still does in some regions). Tunisia is considered the success story of the Arab Spring, adopting a new constitution in 2014 and holding its first free election that same year. It continues to be a work in progress.

Dollars – We could see how Tunisia would be a budget-friendly holiday destination for anyone coming from Western Europe. Compared to countries like Turkey or Georgia we thought it slightly more expensive. Local markets with limited fruit and vegetable choices certainly had better prices than large grocery stores, and had we wanted to pluck a chicken, the local butcher shops were far more economical than cellophane-wrapped breasts in the Carrefour – I was willing to pay any premium for that convenience! Airbnbs were more reasonably priced than hotel rooms. Entry fees for historical sites were exceedingly low, between $3.50 CAD / $2.50 USD and $5.75 CAD / $4 USD, and the daily rate for our car rental was only $39 CAD / $28 USD. The price of gas was a very pleasant surprise – $1.11 CAD/liter / $3.20 USD/US gallon!

| Cost/Day (2 people/12 nights) |

What’s Included? | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic living expenses | $152/day Canadian ($109USD / €103) |

Accommodation, sightseeing/entertainment, groceries, restaurants, car rental, road tolls, and gas |

| All-inclusive nomadic expenses | $198/day Canadian ($141USD / €134) |

Basic day-to-day expenses plus: travel expenses from Juan-les-Pins to Tunis, data packages, subscriptions (Netflix and other streaming services, website hosting, Adobe Lightroom, VPN, misc apps, etc.), and health insurance |

Environment – Other than one night on the road, we stayed in Airbnbs, all of which were newish construction and included secure parking for our rental car.

We drove a counterclockwise loop around northern Tunisia, beginning and ending near the airport in Tunis. We spent the first three nights in the city of Ariana, one of the four governorates comprising Grand Tunis. The Tej El Molk residence (nightly rate: $71 CAD / $52 USD) was a great base not only for access to the historical sights in Tunis, but also for exploring outside the city limits. We opted to be closer to the airport for our last two nights in the country, staying in Mutuelleville, a Tunis suburb full of embassies (nightly rate: $55 CAD / $39 USD).

From Ariana we headed west, spending one night in the Hotel 1001-Nights Palace, a family-run oasis perched above the tiny town of Nebeur (pop. 5500), just north of El Kef. The nightly rate of $117 CAD / $84 USD was a bit of a splurge, however, the hotel we had originally booked in El Kef canceled at the last minute and we were left scrambling.

Given the hotel’s somewhat isolated location they offered fresh homemade meals, and we took advantage of this opportunity to sample some traditional Tunisian cooking. Both the dinner and breakfast were scrumptious, although one bite of the zesty Mechouia salad (grilled peppers, onion, and garlic ground together with additional spices, then topped with tuna, olives, and a boiled egg) almost made me cry. It gave Howard a short-lived case of hiccups before he enjoyed the rest of the dish all to himself.

The southernmost spot we stayed was in the coastal town of Rejiche (pop. 8,925), a bedroom community south of the much larger city of Mahdia. The beach is what brings most tourists to this spot. In November it was just us and the chickens wandering the streets, but it was a logical stop after a long day of driving and sightseeing from Nebeur. It was also close to the El Jem amphitheater (a must-see for any fan of Roman ruins) and had an attractive nightly rate: $50 CAD/ $36 USD.

After a week of fairly intense sightseeing we opted to slow down and spend a few days in the resort town of Hammamet on the Cape Bon peninsula. It is one of the more popular beach destinations in Tunisia, and its population of just over 100,000 quadruples in the summer. It was virtually deserted in November. Our unit (nightly rate: $86 CAD / $62 USD) was set slightly back from the beach and we found it very restful listening to the waves crashing on the shore.

Tips, Tricks & Transportation – Given the number of sites we wanted to visit, we figured renting a car made far more sense than hiring drivers.

This is the 29th country in which Howard has braved the roads, and while not the best driving conditions we (that would be the “royal” we) have encountered, definitely not the worst (that would be Bali, followed by Georgia). There is a certain degree of “better to ask for forgiveness than permission” by drivers merging into traffic, though it’s not disconcerting and aided greatly by the fact that no one is driving particularly fast (except maybe the yellow cabs). Many of the lane markings have long since faded from sight, and jaywalking is customary.

Howard had been forewarned about random speed bumps that could damage your car if you hit them going too fast. They aren’t “random.” They were always preceded by a 30 kph sign and sometimes still had their bright yellow markings, you just had to be paying attention.

For the most part, the driving directions provided by Google Maps were great, though that app does have a propensity for suggesting the “fastest” route which might look like a road on a map yet in reality is not, or at least not anymore. Howard was occasionally forced to reroute himself back onto solid asphalt (switching to “satellite view” was often helpful in that regard as it was easy to spot the paved roads).

We rented our car through a local agency, Camelcar, which had terrific reviews and was far less expensive than booking with any of the big global companies. We were given a Dacia Sandero Stepway that was a few years old, and, serendipitously, is the same model we’ve reserved with Renault (the parent company of Dacia) on an 80-day lease next spring in Europe. It will serve us well.

If you don’t rent a car, I would suggest you pay close attention to whether there are supermarkets or fresh markets within walking distance of your accommodation. Big hypermarkets like Carrefour or Monoprix were scarce in residential areas and we were most appreciative of having a set of wheels to reach them.

Out and About

The ancient city of Carthage, founded by the Phoenicians (from modern-day Lebanon) in the 9th century BCE, once stood on the easternmost edge of the sprawling metropolis of modern-day Tunis. The Carthaginians dominated the western and central Mediterranean Sea. Their colonies stretched across the top of Africa from modern-day Libya to Morocco, up the Iberian Peninsula (Spain), and included the islands of Malta, Sardinia, Corsica, and portions of Sicily. They were invincible until they crossed paths with an unstoppable force. Between 264 and 146 BCE, Rome waged three wars against Carthage.

Rome, at the time, did not have much of a maritime presence, but was attempting to rectify that. Their seafaring efforts were being thwarted by Carthage, who would seize any ship found in their waters and drown the crew. The First Punic (the Latin equivalent of Phoenician) War was Rome’s response to these tactics and the animosity escalated from there. The first two Wars took place in territories outside the Carthaginian homeland. Despite the serious damage inflicted by the Carthaginians, including when Hannibal and his elephants crossed the Alps and laid siege to the Italian mainland for roughly 14 years, they proved to be the weaker opponent and were forced to sue for peace in both those wars, ceding land with each loss.

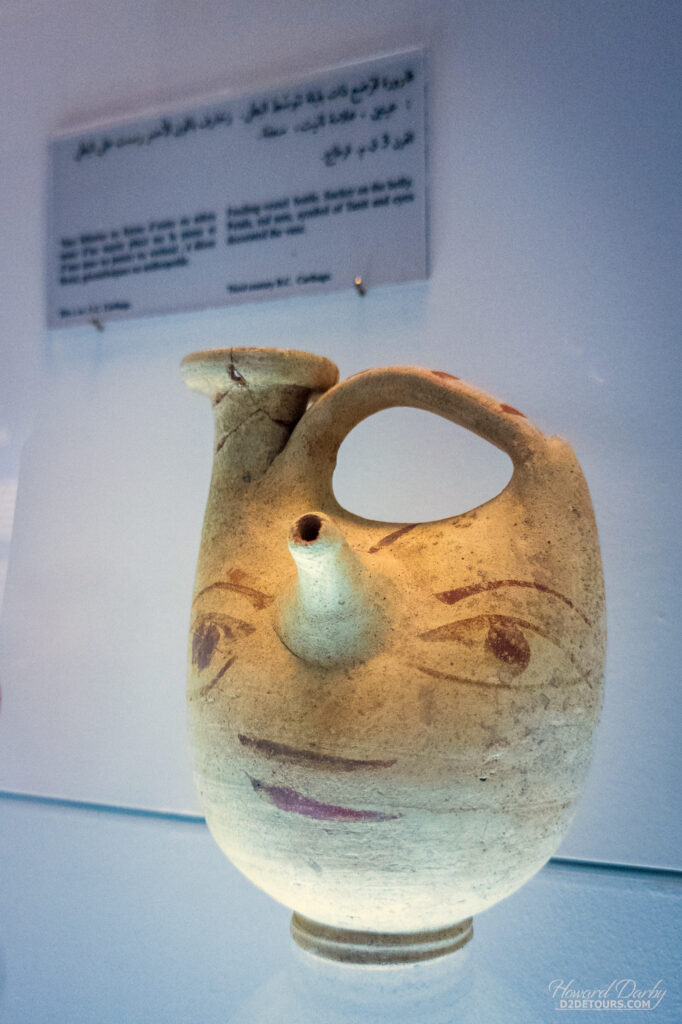

The year 149 BCE marked the beginning of the end, and was fought entirely in what is now Tunisia. In 146 BCE Rome sacked the city of Carthage. The claim that they salted the earth following their victory, to ensure Carthage could never rise again, is not supported by any historical evidence. It is widely viewed as a modern literary device. Still, they did slaughter or enslave the entire population and destroy every trace of Carthaginian culture they could find. Those actions have made it very difficult for historians to piece together an accurate portrait of who the Carthaginians really were (history is written by the victors). The fragments that have been discovered certainly reflect some of their ingenuity – like the precursor to a modern “sippy cup.”

Africus would become one of the wealthiest Roman provinces, second only to Italy, thanks to grain and olive oil exports. The stunning collection of mosaic flooring on display in the Bardo National Museum in Tunis reflects some of that wealth.

The thrill I get from gazing at these masterpieces may rival my obsession with Roman theatres. It was particularly exciting to catch glimpses of this flooring fighting with the dirt and weeds in several of the historical sites we visited.

The Bardo Museum has a tragic recent past. In 2015, two ISIL militants attacked the museum. Twenty-two European tourists were killed in the ambush – a severe blow to the Tunisian tourist industry, which was only exacerbated by Covid. Tourism is slowly making its return, and interestingly the security risk level is no higher than most of the rest of Europe. There is definitely a visible security presence (we even had our car searched before we could enter a mall parking lot) but at no time did we feel even remotely unsafe anywhere in the country.

While most of our sightseeing revolved around ancient sites, we did find some recent ruins on Rimel Beach (aka the Beach of the Wrecks), about 85 km / 53 miles north of Tunis near the city of Bizerte.

We also ventured to the northernmost point on the continent of Africa, Cap Angela – where the wind gusts were so strong it was occasionally hard to stand upright.

Now back to our regularly scheduled program of ancient Roman ruins … Tunisia is full of them, mostly built on Punic foundations.

One hundred years after Carthage was razed to the ground, Rome decided they shouldn’t let a good thing go to waste and returned to build their own version, Latin Carthāgō. By the second century CE, it had regained its prosperity. The Baths of Antoninus, dating from 146 CE, are the largest of their kind outside of mainland Italy. Public baths were clearly an important part of daily life for the residents of Africus; each of the ancient cities we visited had massive complexes (often more than one)!

While Rome may not have been eager to establish a new colony on the site of Carthage, they did quickly begin Romanizing the inland Punic cities. Unlike Carthage, the Romans did not eliminate this indigenous population. Instead, they settled alongside them and over time the peregrini (the non-Roman citizens) began adopting the customs of the colonists and were ultimately granted citizenship.

The city of Dougga (aka Thugga) was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997 as it represents “the best-preserved Roman small town in North Africa.” Somewhat isolated on a plateau out in the countryside, its monumental architecture has escaped the total destruction similar sites have suffered due to urbanization. Many of the streets are still paved and we followed the same paths people going about their daily lives did 2000 years ago.

Though not as extensive as Dougga, Bulla Regia is another well-preserved town. Its preservation is largely due to having been abandoned following an earthquake (likely in the 5th or 6th century CE) and it was lost to the drifting sands. The unique feature of this site is the subterranean rooms dug by homeowners to escape the summer heat. These basements were just as spacious and lavish as their ground-level counterparts. Only a handful of the surviving Bulla Regia floor mosaics have been left in situ, the rest are on display in the Bardo.

The Makthar archeological site was not particularly well-preserved, but we drove right past it on our way to Rejiche so couldn’t pass up the opportunity to stop and stroll amongst more ruins.

The El Jem Amphitheater was built around 238 CE in the city of Thysdrus, the center of olive oil production under the Romans. It had a seating capacity of 35,000 (the Colosseum in Rome seats 50,000), which is a testament to the wealth and importance of the city. Climate change over the centuries slowly decimated the olive oil industry and Thysdrus was ultimately abandoned. By the 10th century, most of its buildings had been cannibalized for construction materials in nearby thriving communities. The amphitheater, however, would remain largely untouched until the 17th century when its stones were deemed necessary for the restoration and expansion of the Great Mosque in Kairouan. The city of El Djem, with the amphitheater at its center, was established by the French in the 19th century.

The last Roman city we visited was Uthina, enroute back to Tunis. While Dougga is a compact 160 acres, Uthina, with a circumference of three miles, is an example of urban sprawl. Granting land to retiring military veterans was a typical form of compensation for Roman troops and ensured they would have the means to sustain a livelihood following their service. Uthina was established for that purpose, likely sometime between 27 and 14 BCE. It had all the accouterments of an affluent Roman city: baths, large villas, a theatre, and an amphitheater (only slightly smaller than the El Jem). Interestingly, unlike other ruins in Tunisia, none of its paved roads have survived, and despite being an archeological site with paid admission was full of grazing sheep and freshly plowed fields.

We did expand our search for history beyond just the Romans. Two hours west of Rejiche is the city of Kairouan, the birthplace of Islam in the Maghreb (North Africa). Construction of its Great Mosque, upon which all later mosques in the region would be patterned, began in 670 CE in conjunction with the founding of the city. Kairouan is still one of the spiritual capitals of Islam. Unfortunately, our visit to the city landed on a Friday, the holiest day in Islam. We were too late in the day to be allowed into the courtyard of the Great Mosque, although Howard was permitted to snap a quick picture from the doorway. So instead we wandered the twisting alleyways of the medina led by an unwanted guide who couldn’t take a hint and then wanted a small tip to leave us alone.

Roughly 161 km / 100 miles south of Carthage lies the city of Sousse, on the Gulf of Hammamet. A much older Phoenician colony than Carthage, it would be eclipsed by its northern neighbour in terms of power and prestige. It would get its revenge centuries later by supporting Rome in its final battle with Carthage and was granted special privileges in the aftermath of the Third Punic War. During the early days of the Arab Conquest of Ifriqiya (Africa), ribats (small fortifications that also included a mosque) were established at regular intervals along the coastline. These fortresses not only housed warriors, their watchtowers served a dual purpose as signal tower and minaret. The Ribat of Sousse, built between the 8th and 9th centuries CE, is the oldest and best-preserved structure of its kind in North Africa.

Us – During my short stint as a school librarian, one of my jobs was working with small groups of children who needed a bit more of a challenge than what the regular curriculum offered. One year a group of grade three students was researching a “Tunisian Holiday.” We priced out airfare from Calgary, how much a nice hotel might cost, what kind of food Tunisians eat, and, most importantly, what one should see and do in Tunis. I was just as captivated as the kids were with the ruins of Dougga and the mosaics in the Bardo Museum, but never imagined it would be some place I’d visit. Fast-forward twelve years, and here I am. While we don’t feel the need to return, it has been an intriguing country to see and more than satisfied my obsession with anything related to the ancient world. Off on a Transatlantic cruise to Miami!

Restaurants – Canned tuna is a Tunisian staple, which was clearly evident in every grocery store we saw.

It finds its way into or onto just about every dish, and is the key ingredient in a popular street food, Brik (breek) – filo pastry filled with mashed potato, parsley, tuna, and egg, then deep fried. When ordering you can stipulate whether you want the egg mrowba (runny) or tayba (cooked). Either way, this hot pocket is a salty, satisfying snack.

In addition to the grilled pepper salad that was served as part of the traditional Tunisian meal we sampled in Nebeur, we also had Shorba (aka Chorba), a carrot, celery, tomato, and chickpea soup seasoned with turmeric, cumin, coriander, and mint found on every dinner table during the 30 days of Ramadan. Our main course was ojja, a cumin-spiced sauce of tomatoes, chili peppers, and onion smothering small chunks of chicken (similar to shakshouka which is made with eggs). It was delicious and despite the chili peppers nowhere near as spicy as the mechouia salad. Both ojia and mechouia are eaten with kesra, a soft chewy flatbread that negates the need for a fork or spoon.

Speech – Arabic is the only official language in Tunisia, however, after 75 years of colonial rule approximately 60% of the population is also literate in French. Secondary education is taught in French, and alongside Modern Standard Arabic is used on most signage (stores, roads, menus). Other than one very elderly lady who we think was trying to tell us we couldn’t park where we stopped, everyone greeted us with a Bonjour. People involved in the tourist industry also spoke limited English. I confess, rather than brushing up on the few Arabic words we know, when English failed us we defaulted to the words and phrases we’d been using for the last month in Antibes, France.

- Bonjour (Bohn-zhoor) – Hello;

- Bonsoir (Bohn-swahr) – Good evening;

- Ça va (sah | vah) – How are you?

- Je vais bien, merci (Zhe | vey | byen | mare-see) – I’m doing well, thank you;

- Au revoir (Oh-rev-whah) – Goodbye;

- Bonne journée (Bone | zhoornay) / Passe une bonne journée (Pass | oown | bone | zhoornay) – both of these phrases mean have a nice day, yet using passe une bonne journée seemed to elicit a friendly reply;

- S’il vous plaît (sill | voo | play) – Please;

- Merci / Merci beaucoup (Mare-see / Mare-see | bow-coo) – Thank you / Thank you very much;

- Pas de quoi (Pah | de | kwah) – You’re welcome;

- Da rien (duh | ree-en) – No problem;

- Oui (wee) / Non (noh) – Yes / No;

- Je voudrais (Zhe | voo-dray) – I would like …

- Je prendrai (Zhe | prawn-dray) – I will have or I will take …

- Celui-là (m) (cel-wee-la) or celle-là (f) (cell-la) – That one (with the difference being whether the item in question is feminine or masculine – another level of complexity in French!)

- Combien ça coûte? (Com-byen | sah | coot) – How much is it?

- C’est tout (Say | t0o) – That’s all or that’s it;

- Numbers – zéro (zeh-ro) / un (uh) / deux (duh) / trois (twah) / quatre (kat-ruh) / cinq (sank) / six (cease) / sept (set) / huit (wheat) / neuf (nuhf) / dix (dees);

- Excusez-moi (eh-skoo-say | mwa) – Excuse me (when trying to get someone’s attention);

- Pardon (Par-d’aw) – Sorry (when moving past someone or as an apology).

Pingback: Howard's Favourite Photos From 2024 - D2 Detours

Pingback: Abandoned Places: Our Favorite Travel Spots! - D2 Detours