Of the 27 countries that constitute the European Union, there are only a handful we haven’t visited. Poland was one of them, and we can now check it off as the 57th country in which we’ve set foot.

While a diverse group of ethnic tribes moved through what would become modern-day Poland (Germanic, Celts, Balts, nomadic tribes from Iran), it was a Western Slavic tribe, the Polans, which translates to “people living in open fields,” who settled the region in the early Middle Ages. Official statehood came in the 10th century, coinciding with the Christianization of the local tribes. While Poland had achieved a certain level of prosperity in its own right, the amicable union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Duchy of Lithuania in 1569 created one of the largest, most populous, and politically powerful countries in Europe, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

All good things come to an end, and Poland’s lack of significant natural barriers (like mountains or large bodies of water) left it vulnerable to invasion. In 1795, after decades of increasingly aggressive invasions, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned between the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy. Internal revolution, and the First World War, severely weakened those empires allowing Poland to regain its independence in 1918. On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded from the north, south, and west. Sixteen days later the Soviet Union invaded from the east. The Russian invasion into Poland was conducted in accordance with secret terms contained within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression agreement signed by Hitler and Stalin in late August. Poland was once again partitioned, with the Russians controlling the land in what is now present-day Belarus and Nazi Germany occupying the remaining Polish territory.

Hitler’s ambition, and his willingness to breach agreements, knew no bounds, and very shortly (1941) he invaded the Soviet-occupied region of Poland, which the Russians did not regain until 1944. The Republic of Poland, later the Polish People’s Republic, emerged from WWII not as an independent state but as a Soviet-controlled buffer zone between the 15 states of the USSR and the Western world – Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and East Germany completed the buffer zone. As communism crumbled in 1989, the Polish government began the steps necessary to transition to a democratic form of government and a market economy, holding their first free parliamentary elections in 1991. The Republic of Poland joined NATO in 1999 and became a member of the European Union in 2004.

Dollars – For a European country we found Poland very budget-friendly. We did choose to stay within walking distance of the historic town centers which increased our accommodation costs (averaging just under $85 CAD /$62 USD per night), but that was nicely offset by the low cost of busing between the cities rather than flying. For both of us, the total cost of busing from Dresden to Wrocław to Warsaw to Kraków was roughly $180 CAD ($131 USD), and we paid a slight premium to be in front-row seating on each trip. We also rented a car for one day to drive out to Auschwitz and still managed to come under our desired daily allowance.

| Cost/Day (2 people/21 nights) |

What’s Included? | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic living expenses | $134/day Canadian ($98 USD / €90) |

Accommodation, Flixbus, groceries/wine, restaurants, local transportation (including a car rental), and visiting Auschwitz |

| All-inclusive nomadic expenses | $149/day Canadian ($108 USD / €99) |

Expenses above plus: subscriptions (Netflix and other streaming services, website hosting, Adobe Lightroom, VPN, misc apps, etc.), health insurance, and a haircut for Whitney |

Environment – In both Wrocław and Warsaw, we had Airbnbs beside city tram tracks, but everything we needed was easily reached on foot so did not avail ourselves of public transportation. Interestingly, both those Airbnbs had minor flaws, with hosts that made no effort to rectify them. The unit in Wrocław was brand new with very comfortable furnishings and a well-equipped kitchen, but the blind on the bedroom window was missing. We managed to clip a thin blanket to the brackets for the missing blind, thus avoiding subjecting our neighbours to a nightly striptease, however we were disappointed that after mentioning the absence of the blind to the host they never offered to deliver a replacement – and we stayed for seven nights! The Warsaw Airbnb was also comfortably furnished, yet the layout was the complete opposite of the listing photos on Airbnb. The couch was in the kitchen alcove, with the dining room table and hard-backed wooden chairs positioned in front of the TV in the living room. We reached out to the host noting the discrepancy between the listing and the reality and were told to leave everything as we found it and “enjoy our stay.” We carefully moved the couch out from the alcove and just put it back when we left. Not a huge deal and our stay in Warsaw was only three nights.

We had decided to just accept that minor inconveniences were going to be a theme in Polish Airbnbs when we arrived in Kraków. Everything about this unit was top-notch (there was even an immersion blender in the kitchen!), and despite its city center location the neighbourhood felt very residential – perfect for Sunday strolling. How fortuitous that Kraków was our longest stay at eleven nights.

Tips, Tricks & Transportation – As we did across Germany, we used Flixbus to move around Poland. We continued to be impressed with their service and price point and particularly enjoyed only having to be at the bus station 15 minutes before departure.

Speaking of price, for some reason it is significantly less expensive to fly out of Kraków rather than Warsaw, so worth keeping that in mind if you’re planning a trip to this country. And while we’re on the topic of transportation, we opted to rent a car for a day trip to Auschwitz, which is roughly 70 kilometers / 43 miles west of Kraków. Organized group tours from Kraków to the Memorial include transportation, but if you prefer your independence as we do, public transportation while doable was awkward, and not entirely economical (it’s not on a Flixbus route, darn it). For just a few dollars more, the flexibility of a car was money well spent.

Throughout the week different museums in Kraków offer free admission (details can be found using this link). There are a limited number of tickets available on those days (and reduced operating hours) so for the more popular museums (like Schindler’s Factory and the Underground Museum) you will want to ensure you arrive well before the doors open and expect to join a queue.

Experience has taught us to check whether supermarkets are closed on Sundays and plan our grocery shopping accordingly. Poland is one of those countries with no Sunday shopping, though fortunately Żabka stores, the Polish equivalent of 7-11s, are open 7 days a week if you happen to arrive in-country on a Sunday.

Out and About

Wrocław

“Vrot-swahf” is a university city with a population of close to 675,000, 130,000 of whom are students. It is filled with a fresh, vibrant energy. Many brilliant minds have graduated from its universities, nine of whom also became Nobel Prize laureates. Various kingdoms have laid claim to the city over its history, beginning with the Kingdom of Poland in the 11th century. It was then part of the Kingdoms of Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic), Hungary, Habsburg, and Prussia before becoming the sixth largest city within the newly unified German Empire (1871). As a German city it was known as Breslau because Vrot-swahf tied German tongues in knots. A sizable segment of the population embraced the far-right ideology of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party with 44% of the population voting for the Nazis in 1932, which did not bode well for the ethnic Pole and Jewish populations.

For most of the WWII, Breslau/Wrocław was well behind the frontlines. That changed in August 1944. With Russian forces pushing further West, Hitler decreed that Breslau be held at all cost. Tens of thousands of civilians died during the three-month Siege of Breslau and half the city was destroyed. In May 1945 it was the last city in Germany to surrender and in August was placed under Soviet control.

While the bulk of the city’s German population was relocated to post-war German states established under the terms of the Potsdam Agreement, the last German school wasn’t closed until 1963. Still, rebuilding Wrocław immediately following the war was a concerted effort of “Polonization” and “de-Germanization.” Gothic architecture was painstakingly restored whereas buildings reflecting the Baroque style favoured by the Germans were left to crumble or outright destroyed.

One of the German buildings that did escape unscathed was the Centennial Hall, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006. Built to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig, it opened in 1913 as a venue for exhibitions, sporting events, concerts, and theatrical performances, which continues to be its purpose today. UNESCO has recognized it for its “pioneering work of modern engineering and architecture … becoming a key reference in the later development of reinforced concrete structures.”

The fountains behind the Hall dance to light and music with hourly performances every day from 10 am until 9:40 pm.

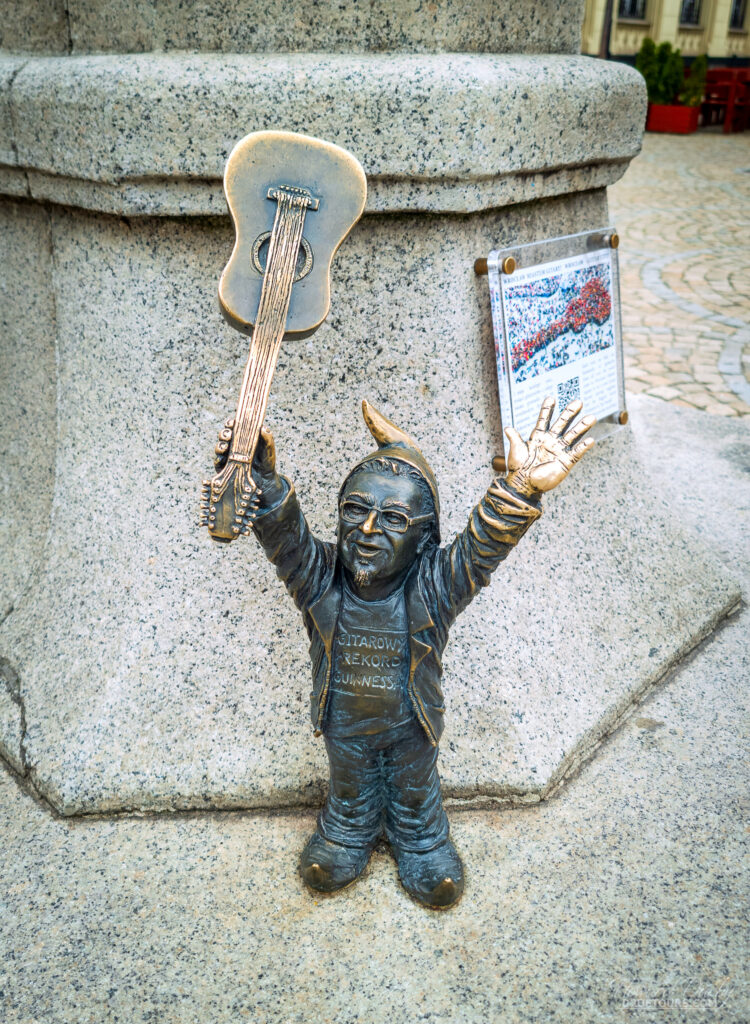

Hundreds of foot-tall bronze dwarfs are hiding in plain sight around Wrocław. The “Orange Alternative” was a political movement born in the 1980s in response to growing discontent with the communist government. Where antigovernment graffiti had been blackened out, the group began painting silly depictions of dwarves daring the government to waste resources covering something as trivial as a storybook character. In 2001, a commemorative bronze dwarf was placed on Świdnicka Street and they began to multiply – currently there are over 400 scattered around the city.

Warsaw

Warsaw, the capital of Poland, is classified as a global city – an “urban center that has a significant influence on the global economic, cultural, and political landscape.” New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo share that same designation.

It hasn’t been an easy path to success as this city has seen more than its fair share of destructive events, courtesy of Mother Nature, plagues, and invasions, the most recent of which began in 1939. When Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Hitler had his eyes set on Warsaw. Under the Pabst Plan, an early blueprint for German colonization of Central and Eastern Europe, Warsaw, with its 1.5 million inhabitants, would cease to exist. It would be replaced with Neue Deutsche Stadt Warschau (New German city of Warsaw) home to no more than 130,000 ethnically pure Germans who would be serviced by a Polish labour force.

Warsaw surrendered to Germany on September 27th. The Pabst Plan was implemented in stages, with the first stage being simple structural reconstruction. The second was population reduction. In October 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was established. Roughly half a million people were relocated into an area measuring 2.6 square kilometers (1 sq. mi). And if cramped living conditions weren’t cruel enough, the daily per-person food ration was the equivalent of 183 calories.

On April 19, 1943, orders directing the implementation Hitler’s “Final Solution” arrived; the Jewish Resistance responded. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the largest single revolt by Jews during WWII, only to meet with failure 29 days later. Approximately 13,000 Jews lost their lives during the Uprising, and the survivors were deported to concentration camps where, for most, death soon followed.

Warsaw however wasn’t done resisting German occupation. One year later, the Home Army (Polish resistance) staged a 63-day uprising, capitalizing on the chaos of the German retreat in the face of advancing Soviet troops. Tragically, once again, the insurrection failed, due in large part to neither the Western Allies nor the Soviets offering any support. The human losses were catastrophic and the Germans were so enraged by the revolt they retaliated by razing the city center to the ground. Still, the Polish spirit prevailed. In the five years following the War, Warsovian citizens meticulously restored their Old Town remaining faithful to original plans for buildings dating as far back as the 13th century.

Kraków

One of the oldest cities in Poland, “Kra-kuhf” first appears in the annals of history in 965 CE where it is noted as being a much older commercial center. While Mongol invasions in the mid-13th century destroyed much of the city, by the end of that century it had been rebuilt and those buildings still stand today, largely undamaged by WWII. Kraków’s historic city center was one of the early additions to UNESCO’s list of heritage sites, being added in 1978. It was the capital of Poland from the 10th century until the end of the 16th century when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed and Warsaw was named the capital.

We took advantage of the free days offered by several of the city’s museums and learned more about Kraków from three different perspectives.

The Rynek Underground Museum, located beneath the Old Town Market Square, offers a glimpse into what that same square looked like seven hundred years ago through artifacts and multimedia presentations.

The exhibits inside the Krzysztofory Palace paint a picture of Cracovian culture, including its myths and legends, my favourite of which was that the droves of pigeons occupying the Market Square are just enchanted soldiers awaiting the return of their ambitious, albeit selfish, prince.

Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory is an extraordinary museum. Housed in the factory’s administration building, only a very small portion of the museum deals with who Oskar Schindler was (he was a scoundrel) and what he did for the Jewish community of Kraków (he saved roughly 1,200 people). The bulk of the collection relates to Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland and the devastating consequences, detailed through anecdotal evidence and actual artifacts. Powerful is an understatement.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum was not free, approximately $37.50/pp CAD – worth every penny!

Soon after Germany invaded Poland, the Nazi’s security force, the SS, converted an old army barracks in Oświęcim (the German pronunciation of which is Auschwitz) into a prisoner-of-war camp. For the first two years, Auschwitz I was a revolving door of almost exclusively Polish detainees, who were quickly used up through forced labour. In the summer of 1941, a concentration and extermination camp was added – Auschwitz II (aka Birkenau). Beginning in 1942, and continuing until late 1944, Jews from German-occupied Europe were crammed onto freight trains bound for Hell. Of the 1.3 million people sent to the Auschwitz complex,1.1 million were murdered.

While you can visit the museum independently, joining a guided tour is highly recommended to understand the scope of the genocide. It is a lot to absorb over the course of 3.5 hours; the horror is unrelenting as you pass through room after room, in building after building. Even the birds seemed to respect the solemn nature of this memorial. The crunch of the gravel under the soles of our shoes was the only sound accompanying our walk between structures, echoing the millions of footsteps before us.

In 1945, with the Soviets on their doorstep, the Nazis tried to destroy the evidence of their atrocities by blowing up the Birkenau gas chambers, burning down most of that camp, and forcing the ambulatory camp population on a death march west. In 1947, the Polish government established the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum on the site of Auschwitz I and Birkenau.

Us – We liked all three Polish cities we visited, with Kraków probably being our favourite, followed closely by Wrocław. Warsaw felt more business-like; Kraków and Wrocław each had a carefree undercurrent. That’s not to say we didn’t find all of the Polish people rather stoic, they most certainly are, yet more than willing to answer questions or offer help. We’d like to come back and explore some of the regions further north. Off to Istanbul!

Restaurants – I’m not sure you could visit Poland without sampling some pierogi, at least once. We had dinner at Gościniec Polskie Pierogi in Warsaw where I enjoyed a plate of potato and bacon fried pierogi, with a liberal helping of sour cream, and Howard struggled to finish his heaping portion of potato dumplings (similar to gnocchi), pork stew, peppers and mushrooms. Definitely “stick to your ribs” food.

Speech – According to linguists, Polish is one of the more difficult languages for native English speakers to master. The good news is that the writing is phonetic once you learn to properly pronounce those “z” digraphs, and understand how a squiggle changes the sound!

| ‘ą’ sounds like ‘on’‘ę’ like ‘en’

‘ł’ like the ‘w’ in ‘win’ ‘ń’ like the ‘ny’ in ‘canyon’ ‘ó’ and ‘u’ like ‘oo’ in ‘boot’ ‘w’ like the ‘v’, unless it’s at the end of a word, then it’s softer like an ‘f’ ‘ch’ like the ‘h’ in ‘his’ ‘cz’ and ‘ć’ like the ‘ch’ in ‘beach’ ‘dz’ like the ‘ds’ in ‘beds’ ‘dż‘ like the ‘g’ in ‘George’ ‘rz,’ ‘ż’ and ‘ź’ like the ‘su’ in ‘treasure’ ‘sz’ and ‘ś’ like the ‘sh’ |

Cześć (Cheshch) – Hi

Dżień dobry (Jen doh-bri) – Hello/Good Day Do widzenia (Doh veet-zen-ya) – Goodbye Proszę (Prosheh) – Please Dżiękuje (Jen-koo-yeh) – Thank you Tak (Tahk) – Yes Nie (Nyeh) – No No (Nohe) – Okay Przepraszam (Psheh-prasham) – Excuse me/Sorry |

Pingback: Europe by Car: Part One - D2 Detours