With the Danube river acting as a natural border we crossed from Romania into Serbia at the Drobeta-Turnu Severin – Kladovo bridge crossing. The Romanian border guard was delightful. She apologized for her poor English skills telling us she’d learned it by watching television but really wanted to know what we thought of her country and then wished us continued happy travels; the Serbia guard didn’t make eye contact nor speak to us!

I realized during our visit to Serbia that I am woefully uninformed about this part of the world so you get to learn along with me (or feel free to just move on to Howard’s pictures if this gets dull).

The first mention of “Slavs” comes from 6th century Byzantine chronologers who mention tribal people coming down from the Carpathian Mountains and settling along the Danube. The tribes were described as very hospitable, yet fiercely independent. Between the 8th and 10th centuries these settlements were known collectively as the Principality of Serbia. By the 11th century, the Grand Principality emerged encompassing Serbia, Montenegro, Herzegovina and some of Croatia. By the mid-14th century, Kosovo, Northern Macedonia, Albania and half of Greece were added to the Serbian Empire under the rule of Stefan Uroš IV Dušan (Dušan the Mighty). Internal squabbling following Dušan’s death in 1355 led to the rise of numerous fiefdoms, making the region easy pickings for Ottoman conquest in the 15th century, under whose control it remained for nearly five centuries. In the early 19th century Serbia began to assert its independence from the Turks although it wasn’t until the 1878 Treaty of Berlin that that independence was formally recognized.

The 20th century marks (in my opinion) one long period of ugliness. In 1912, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria banded together to finally push the Turks from the region (the First Balkan War), each laying claim to bits of territory in the aftermath. Bulgaria was annoyed that it lost the Macedonian region, and in 1913 declared war on its former allies (the Second Balkan War). The upshot of that war saw borders once again being redrawn with Serbia emerging as a powerhouse in southeastern Europe. Both wars were marked with some rather unpleasant examples of ethnic cleansing, sadly foreshadowing the years to come. Austria-Hungary had long seen Serbia as a threat to its empire and those worries were exacerbated by the two Balkan Wars. Things came to a head on June 28, 1914, when Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand (and his wife) were assassinated by a Bosnian Serb nationalist; one month later Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and the stage was set for WWI. One of the outcomes at the end of WWI was the unification of the southern Slav territories previously held by the Austro-Hungarian Empire (namely Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina) with Montenegro and Serbia (whose provinces included Kosovo and Macedonia) to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, notably with a Serbian ruler. The Kingdom was renamed Yugoslavia (“Land of the South Slavs”) in 1929.

Post-WWII Yugoslavia, under the authoritarian leadership of Josip Broz Tito, became a federation of six equal republics: Serbia (including its province of Kosovo), Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and North Macedonia, with its seat of government in Belgrade, Serbia. As communist/socialist leaders go, Tito was quite popular both inside his country and abroad. Under his “benevolent dictatorship” Yugoslavia was unified, however his death in 1980 (and the fall of communism nine years later) laid bare old rifts between the republics and renewed the interest in nationalism. Beginning in 1991, brutal civil war, fueled by Slobodan Milošević’s dream of creating a “Greater Serbia,” erupted throughout the region.The conflict between Serbia and Kosovo was particularly nasty. For a variety of reasons, Milošević, and members of his ruling party, resented the rapidly growing Albanian-Muslim demographic in Kosovo who were seeking independence from Serbia. Years of vicious efforts to suppress this ethnic group finally resulted in the intervention of NATO in early 1999. Only after peace talks failed and Serbia renewed their assault on Kosovo did NATO resort to air strikes, the remnants of which can still be seen in Belgrade.

The eleven week campaign by NATO saw Serbia finally withdraw from Kosovo, leaving it under UN administration. In 2008 Kosovo formally declared its independence from Serbia, a status recognized by some of the nations of the world but not all of them, notably Serbia. And so from the remains of Yugoslavia, seven independent countries have emerged: Croatia, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Kosovo.

Serbia applied for acceptance into the EU in 2008 and has been a candidate for accession since 2012, hoping to finally join by 2025. However, its complicated relationship with Kosovo is proving to be a significant obstacle. While driving around Belgrade I noticed several pieces of graffiti – “Serbia=Kosovo” and “remember Kosovo belongs to Serbia,” so 2025 might be optimistic.

And there you have it, 1500 years of history in four paragraphs.

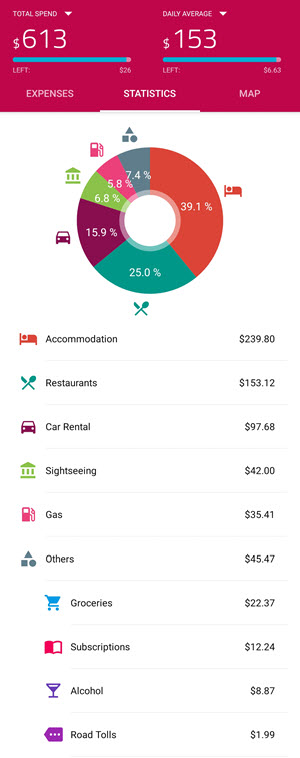

Dollars – We averaged about $153/day Canadian ($117 USD / €115) for 4 nights in Belgrade, which is on the high-end of our budget especially when staying in this region. Had we stayed longer, and prepared more meals ourselves (rather than eating out each night like we did), it would have been very easy to get our expenses down into a more economical range. In any event, even at the high-end of our budget, this only works out to roughly $4,590 per month CAD ($3,517 USD / €3,463), with the bulk of our expenses being accommodation and food.

Environment – We managed to find an Airbnb with free parking right in the city center of Belgrade. It was tiny (much smaller than we anticipated based on the listing’s pictures) but it had everything we needed and we were very comfortable for a short stay. The internet wasn’t great and frequently dropped the connection when we were trying to stream anything (particularly frustrating when I was trying to watch the Belgian F1 race live), but otherwise served our needs completely

Tips, Tricks & Transportation – Toll roads in Serbia operate with physical toll booths, and four motorways are included in the toll network: the A1, A2, A3, and A4. Our route from Romania had us following the Danube on a secondary highway before cutting across to Belgrade and accordingly we were only on the A1 for a short period of time; the toll was 180 RSD ($2 CAD).

Most of the streets in Belgrade’s city center run northeast/southwest rather than north/south. I am completely hopeless when it comes to navigating – drop me in the middle of a city with a map and I’ll just have to die there ‘cause I’ll never find my way out – but it’s second nature to Howard. However even he found this axis somewhat challenging when orienting himself on Google maps.

Although we weren’t preparing meals in our Airbnb, we did wander through the Bajloni Market on Džordža Vašingtona 55 which was full of local (no English spoken here) vendors selling beautiful fresh produce. We picked up a quarter of a watermelon for 140 RSD ($1.55 CAD), using sign language (1 – 4 – 0) to confirm we understood the price, and enjoyed it for breakfast during our stay.

We follow a couple of private Facebook Groups (Senior Nomads and Go with Less) where members often post their current whereabouts on the off-chance paths may cross. We met up with fellow travellers while we were in Brasov, Romania and did so again in Belgrade. It was great fun to connect for a meal, and we also did a day trip together to the outskirts of Belgrade.

Out and About – Serbian State Road 34 follows the course of the Danube, occasionally climbing high above the river to offer spectacular views. The road also frequently has tunnels cutting through the rocky terrain, none of which are lit, just a thin strip of reflective tape running along the inner wall! We ultimately headed toward Belgrade on a road that made Italian highways seem down right roomy before connecting with the A1 Motorway, but the route along the Danube took us past some worthwhile stops first.

Lepenski Vir

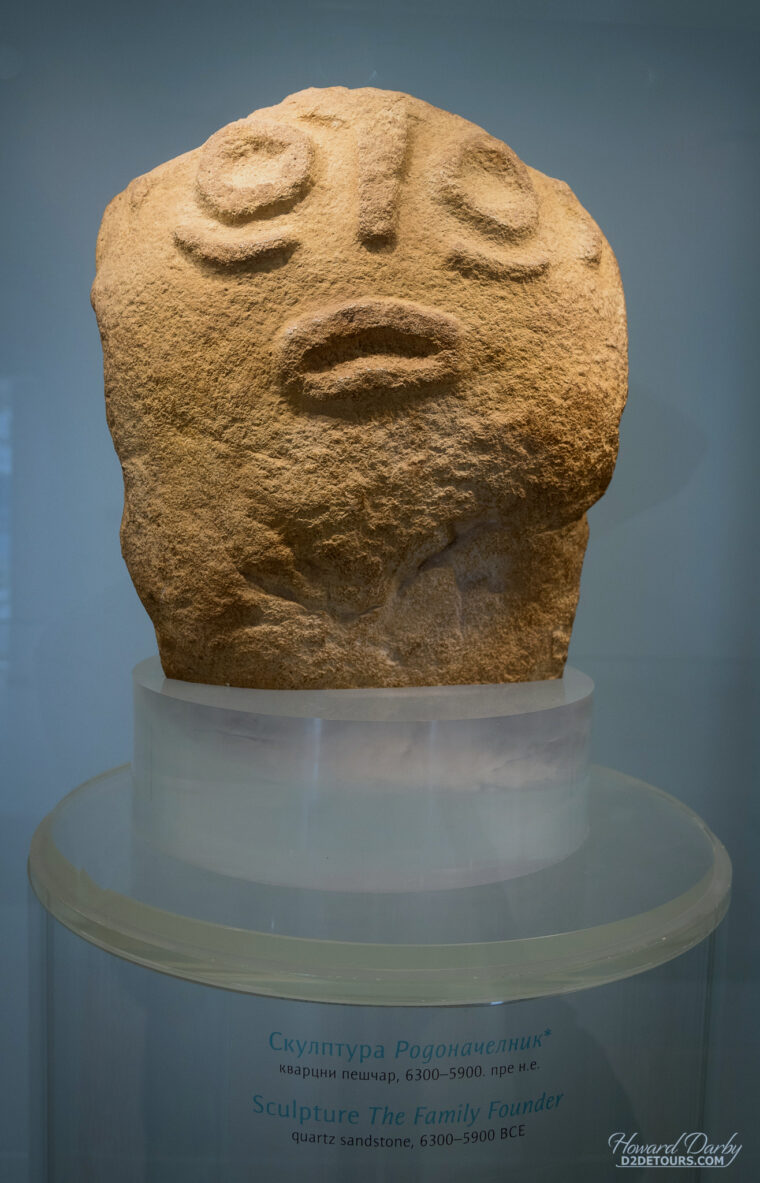

Discovered in 1960 by the landowner, radiocarbon dating suggests this settlement dates between 9500-7200 BCE making it the oldest planned settlement in Europe. Serious excavation occurred between 1966 and 1967 and our visit to the site began with a quirky video documenting that excavation. The visitors’ center is actually a relocated reconstruction as the original location was flooded in the early 70s when the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station was built. While the National Museum in Belgrade includes information about the find, the original artifacts are still housed at the Lepenski Vir site and significant money has been spent creating this interesting museum. The entrance fee was a very reasonable 550 RSD/pp ($5.50 CAD).

Golubac Fortress

Strategically situated at the entrance to the Iron Gates (where the Danube is at its widest before running into a gorge separating the Carpathian Mountains from the Balkan Mountains), it’s not surprising this fortress has been the site of numerous battles. Turks, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Austrians and Serbs have all, at one time, held this position. During the 1930s, the highway was built right through the remains of the fortress leaving it badly damaged and you can still see the old tunnel if you come to the fortress from the West. In the 1970s ,there was some renewed interest in the ruins, but not enough and much of it became overgrown. A public project in 2005 began restoration of the fortress in earnest. The site is divided into four zones. Only Zone I is accessible to everyone, with an entrance fee of 600 RSD/pp ($6.60 CAD), and has interesting historical information. Zones II-IV are only open to adults 18+ and are challenging hiking trails climbing to the top of the fortress, with each Zone becoming increasingly more difficult to traverse, and expensive). We did not have proper footwear (I was just in sandals) so we only did Zone I.

As we were coming from Romania, Lepenski Vir and Golubac were on our route, however you could do both sites as a long day-trip from Belgrade.

Belgrade

Belgrade sits at the junction of the Sava and Danube rivers.

It is the largest city in Serbia (approx. 1.7 million people) and also its capital. Given its location it will come as no surprise that there are the remains of a citadel, which is now an open-air museum in Kalemegdan Park, perched some 125 meters (410 ft) above the rivers.

Kalemegdan Park is the most visited tourist attraction in the City with the bohemian quarter of Skadarlija coming in a close second. Full of restaurants, hotels, art galleries, antique and souvenir shops, this part of Belgrade is a bright and lively area to walk through.

Two lovely examples of Serbian Orthodox churches in Belgrade are St. Mark’s Orthodox Church in Tašmajdan Park and the Temple of Saint Sava on the Vračar plateau.

The Tesla Museum in Belgrade came highly recommended and, frankly, was a disappointment. With an 800 RSD/pp ($8.80) entrance fee it was on the more expensive (relatively speaking) side of tourist attractions and did not meet our expectations. You must do the tour guided, and while the guide did demonstrate a couple of Tesla’s experiments, we didn’t really learn anything that we couldn’t just have easily read on Google. I will confess (now that I understand a bit more about how important ethnicity is to this part of the world) that it was interesting to learn that while Tesla was born in the Austrian Empire, in the village of Smiljan (now modern day Croatia), he is an ethnic Serb. Both countries claim him as a native son, but showing some adept diplomacy Tesla himself was quoted as saying “I am equally proud of my Serb origin and my Croat homeland.” At age 35, in 1891, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

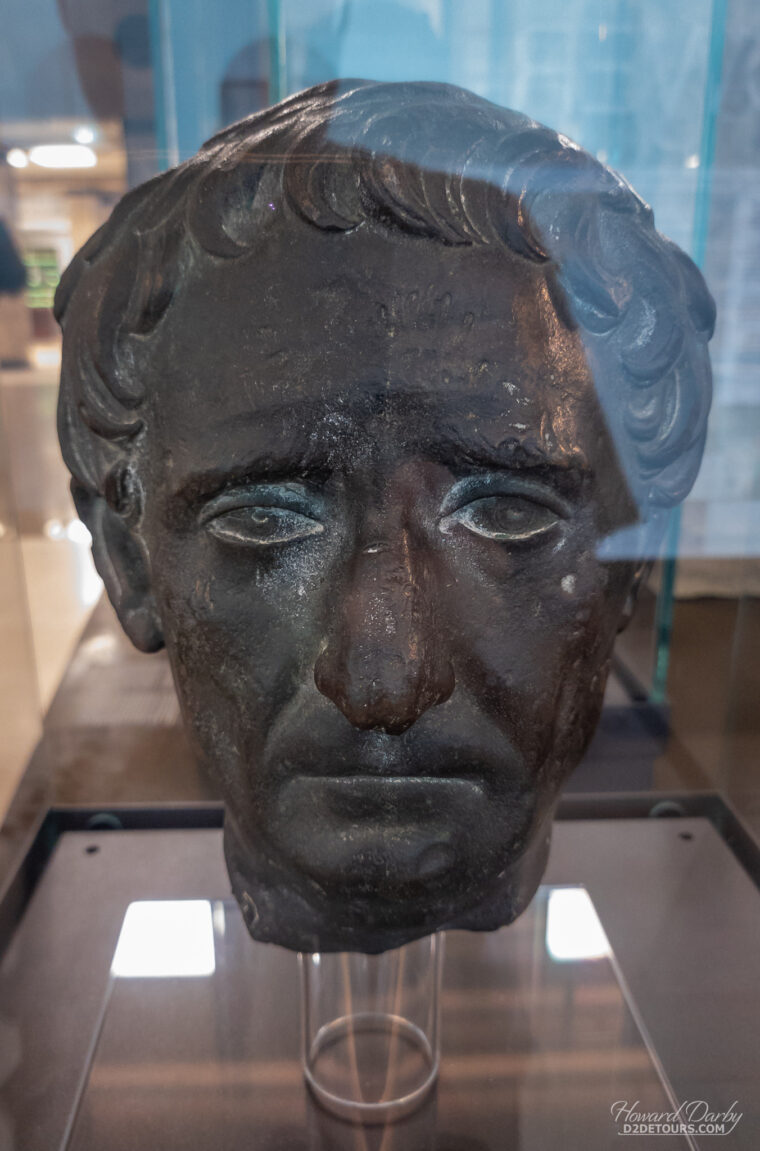

While walking through Belgrade’s main city square, Republic Square, we popped into the National Museum of Serbia (looking for an air-conditioned reprieve) and were delighted to learn that entrance is free of charge on Sundays (the rest of the week it’s only 300 RSD/pp, $3.30 CAD). Even with free admission, it was quite quiet. It’s not a huge museum and is predominately archeological in nature with a couple of numismatic vaults and some 20th century art.

With the benefit of our own car, we did a day trip into the outskirts of Belgrade, starting first with Tito’s Blue Train. We had a helluva time trying to figure out how to get tickets. They are not available at the train yard and a Google review mentioned getting them at the train station, which we took to mean in Belgrade. That proved to be an incorrect assumption so we carried on to the train hoping someone there could provide some guidance. The guide spoke virtually no English, and after it was clear we could not understand her directions to the ticket office, she sighed and indicated we could just pay her, which we did (250 RSD/pp / $2.80 CAD). Given her limited English the tour was not particularly informative (although she was a friendly, cheerful person), but was visually fascinating and I later found an online article that gave an excellent summary of the train, with the visuals still fresh in our mind.

Not far from the center of Belgrade, atop Mount Avala, is the Monument to the Unknown Hero, a memorial to fallen WWI Serbian soldiers. For a few days in October, 1915, a small Serbian battalion on Mount Avala held the line against advancing Austro-Hungarian and German troops before ultimately being overrun. A rudimentary monument had been raised by local villagers following the war, but the Serbian government felt a more dignified monument was required and completed one in 1938. Reminiscent of a sarcophagus, it is a stunning structure that interestingly sports some cannon damage from WWII Russian troops.

Visible through the trees surrounding the memorial is the Avala Tower, a 204 meter (672 ft) tall concrete telecommunications tower. The original tower from 1965 was destroyed during the 1999 NATO bombings with reconstruction of the current tower beginning in 2006. It was officially re-opening in 2010. Eastern bloc countries sure do love concrete monstrosities.

Us (our thoughts on the area) – Belgrade is on the gritty side, but we felt completely safe walking around at night and did enjoy our visit. Would we go back? Probably not. It was interesting for sure, but has a bit of an oppressive feel to it. Off to the Istria Peninsula in Croatia!

Restaurants – While my hips might disagree, my tastebuds were delighted to find baklava again! Kultura Baklava is a Turkish restaurant so it was no surprise that their baklava was pretty darn good, but Balkan Baklava was even better and we succumbed to our weakness for this gooey goodness on several occasions during our short stay in Belgrade.

With only four nights in Belgrade we were a bit lazy about preparing meals at home. We celebrated Howard’s “Beddian Birthday” (your age matches your birth year – turned 61, born in 1961) with an excellent meal at a very reasonable price at the French/Italian restaurant Casa Nova.

We also tried some Serbian street food – pljeskavica – an enormous (about 6” in diameter and 1” thick) burger made with a combination of two meats, either beef, lamb, pork or veal (I had beef and pork) served on lepinja (Serbian flatbread) with sour cream, lettuce, tomato and onion. Messy, but yummy, and definitely two meals worth of food!

Speech – Other than the local market, we found everyone spoke English, but it’s always nice to know a few words in the local language:

- Dobar Dan (do-BAR dan)– Good Day;

- Zdravo (ZDRAH-voh) – Hi;

- Dovidenja ((doh-vee-JEH-nyah) – Goodbye (Ciao works too);

- Molim (Mo-leem) – Please;

- Hvala (hVa-lah) – Thank you;

- Da / Ne – Yes / No;

- Izvini (EEZ-vee-nee) – Excuse Me;

- Pričati li Engleski? (PREE-cha-tee lee EN-gles-kee?) – Do you speak English?

- Ne razumem (neh rah-ZOO-mem) – I don’t understand;

- Koliko je košta? (KOH-lee-koh ye KOH-shta?) – How much does it cost?

- Račun (RAH-choon) – Bill (in a restaurant);

- Izvinite (EEZ-vee-nee-teh) – Sorry.

So sorry you didn’t feel comfortable in Belgrade. If I’d only known fellow nomads visiting I would’ve happily shown you around! You went even to our local green market – we live only 5 min from Bajloni. It’s true that many Serbs don’t speak English as older generation have studied more French, Italian and German.

Btw, Serbia has been an EU candidate already since 2008 and there are still lot of chapters open to negotiate. It’s common disbelief that Kosovo is the thing, but there are much bigger things to solve, for example environmental subjects, rule of law, press freedom etc. if I remember correctly, there are 35 chapters to negotiate before Serbia is ready for the membership status.