A couple of years ago, we spent a week in Stockholm, Sweden, and loved it. This year, with our 2-month leased car from Renault, we ventured deeper into the Scandinavian peninsula, touring a bit more of Sweden, and experiencing Norway and Denmark too.

FYI: Finland is not part of Scandinavia. It, along with Iceland, joins Sweden, Norway, and Denmark under the umbrella of Europe’s Nordic countries.

Takeaways from 30 days of exploration: Stockholm continues to be our favourite Scandinavian city; the Norwegian landscape is spectacular; and Denmark is pretty flat – the country’s highest point is only 171 meters / 560 feet above sea level.

These three nations have a deeply intertwined history. Between the 8th and 11th centuries, the Vikings raided, traded, and settled their way around the world – east to Novgorod (Russia) and Constantinople, south to the Mediterranean (France and Spain), and west to Britain, Greenland, and North America. They had a profound effect on the language, culture, and politics of the people they encountered. By roughly 1050, the last Viking had converted to Christianity, and former chiefdoms had coalesced into the independent Kingdoms of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark as we know them today.

These three kingdoms banded together in the late 14th century to counter the increasingly powerful Germanic trade union known as the Hanseatic League, which was attempting to expand across the North and Baltic Seas. The Kalmar Union, wherein the sovereign states of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden agreed to have their foreign and domestic policies governed by the Danes, lasted from 1397 to 1523. It was a rather tenuous alliance with Sweden regularly threatening to leave, and finally making good on their threat in 1523. Denmark and Norway remained united until 1814, when Norway was ceded to Sweden following the Napoleonic Wars. The United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway peacefully dissolved their union in 1905. All three of the modern-day Scandinavian countries are constitutional monarchies with strong economies and robust social welfare systems.

We took a ferry from Świnoujście, Poland (pronounced sh-vee-no-oo-ish-chye, which fortunately we never had to try to wrap our tongue around) across the Baltic Sea to Sweden. It is a 7-hourish crossing, so we decided a cabin with twin beds and a private bathroom would make for a much more comfortable crossing and, unlike the hideously expensive option of lay-flat seats on an airplane, the cost of a private cabin was negligible. It added less than CA$100 to the price of our tickets (total fare was CA$260), and upon arriving for check-in, we think we mistakenly paid for two cabins when we were attempting to decipher the Polish-language booking website – still, money well-spent!

When putting together our Scandinavian itinerary, it became abundantly clear that staying in Copenhagen, Denmark was going to hit our pocketbook hard; however, we noticed that Malmö, Sweden is connected to Denmark by a bridge across the Øresund Strait. Perfect! We’ll stay in Malmö and just do a day trip to Copenhagen – decision made, on to more planning. Once we got to Malmö we began to organize our Copenhagen day trip, only to discover that the bridge between these two countries is a toll bridge with a CA$106 toll EACH WAY! Parking in downtown Copenhagen for an afternoon was likely going to be upwards of CA$75, and should we be unlucky enough to need any gas in our tank, petrol was running around CA$3.68/litre (USD$10.76/ US gallon). Gulp! FlixBus to the rescue. We have become huge fans of FlixBus. It’s cheap, reliable, and operates throughout much of Europe – they have also expanded into North America. For just under CA$74 total, we took a round-trip bus from downtown Malmö to downtown Copenhagen. Our excursion did still cost us CA$30 for parking in Malmö, and we forked over more than 50 bucks for a couple of pølser (hot dogs), water, and two ice cream cones in Copenhagen.

Copenhagen began as a small fishing village known as Havn in the 10th century. It quickly grew, and by the 12th century was known as København, derived from the Viking word kaupangr (trading place). During the 16th century it was the capital of the Kalmar Union. We thought it was perfect for a day trip, and clocked over 18,000 steps wandering its streets.

Malmö was first mentioned in historical records in the late 13th century, and was known by the inauspicious name of Malmhaug (gravel or sand pile). It was originally part of Denmark and did not become part of Sweden until 1658. Today, it is one of the fastest-growing cities in Sweden.

Malmöhus (Malmö Castle) is one of the oldest surviving fortifications in Scandinavia, although “surviving” is a bit of a stretch. It began as a simple fortress in 1434 enforcing the king’s levy on foreign ships passing through Scandinavian waters. Since then, it has been ravaged, rebuilt, repurposed, and, in 1930, restored. A small section of the original brickwork (white) is visible, contrasting with the red brick restoration work.

One of the tools we use when researching a destination is the World Heritage – UNESCO List app. You can zoom in on its map to find all of the Heritage sites in and around a particular area you’re visiting.

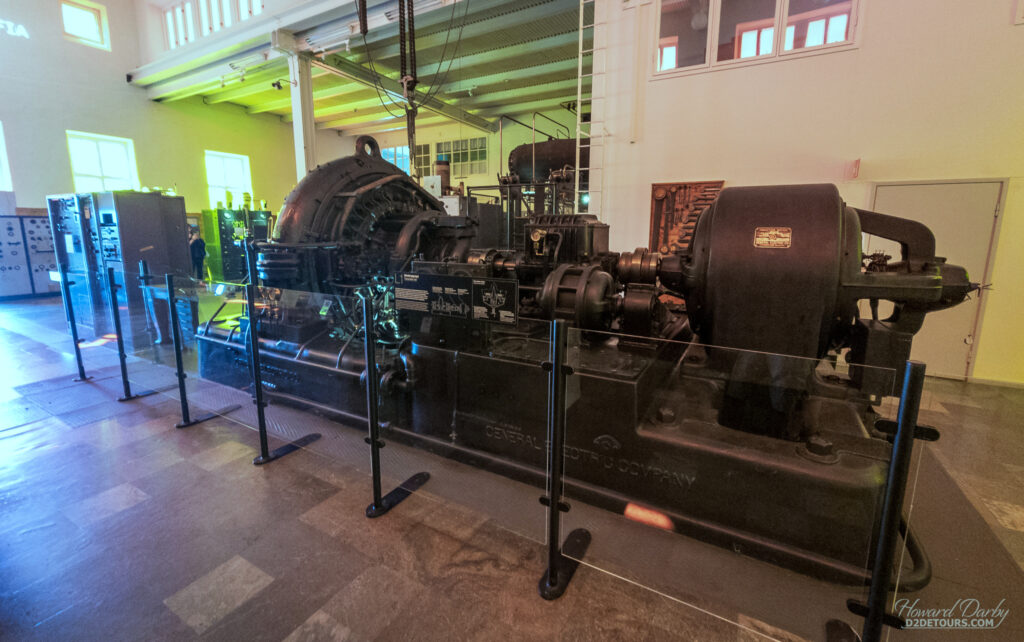

While a large number of the heritage sites recognized by UNESCO are archeological, every now and again there is something from the more recent past, like the Grimeton Radio Station in Varberg, Sweden. Built between 1922 and 1924, it is the “only remaining fully functional example of a pre-electronic, longwave transatlantic radio station using an Alexanderson alternator” (a rotating machine that produces the current necessary for radio transmission). From this station, telegrams using Morse code were relayed to Norway, Denmark, Scotland, and North America. During WWII, it was Sweden’s only telecommunication link with the rest of the world. By the 1960s, most of the transmitters were decommissioned and replaced with modern technology, yet, as UNESCO notes, the original equipment has been maintained and is still operational. I confess I couldn’t grasp 99% of the technical information presented in the museum, but did retain one tidbit: using the technology available in the 1920s, it would take three years to transmit a message similar in size to 1GB of data – modern file sharing services like Google Drive or Dropbox enable users to upload a 1GB-sized file in mere minutes.

In the Swedish province of Bohuslän, on the border with Norway, the granite bedrock scraped clean by receding glaciers made an ideal canvas for Bronze Age artists to leave an impression. To date, 1,500 carving sites have been discovered in the region. Thousands of individual petroglyphs, believed to have been carved between 1,700 and 500 BCE, have been ground or pecked into the rock face. The tiny village of Tanumshede has one of the highest concentrations of these petroglyph panels – 360.

Most of the panels are located on private land; however, four sites: Vitlycke, Aspeberget, Litsleby, and Fossum are open to the public (with no entry fee). They include walking paths with information boards that offer a tiny bit of insight mostly in the form of “what” is depicted rather than “why” it was carved. Perhaps the most impressive panel is the 22 x 6 meter / 72 x 20 foot Vitlyckehäll rock, containing nearly 300 carved motifs.

The original drawings were not coloured. Red paint has been used to make them visible for tourists, which I recognize detracts from their authenticity, but I don’t know if an untrained eye would ever locate a carving on the rock face otherwise.

Oslo reminded us both of Vancouver – a vibrant mix of urban and natural surroundings. It has an extensive park system, many of which are connected by pedestrian walkways, allowing for a seamless stroll through Oslo’s greenery. Its most famous park is Frognerparken, which encompasses the works of Gustav Vigeland (1869-1943).

This rather surreal landscape of 212 granite, bronze, and wrought iron sculptures was conceived as a gift to the citizens of Oslo – the city provided the land and Gustav the art. He began his life’s work in 1924, and continued producing these sculptures depicting the human experience until his death in 1943.

We stayed in one of Oslo’s suburbs, Bærum, 30 km / 17 miles from the center of Oslo. Fortunately, the city has an excellent public transportation system that not only connects to the suburbs but also includes the small passenger ferries navigating the waters in the Oslofjord.

We enjoyed a bright sunny afternoon island hopping in the fjord. Hovedøya, a quick 6-minute ferry ride from Aker Brygge (Oslo City Centre), is a popular destination for a day of swimming and picnicking. It also has the ruins of a 12th-century monastery, and a few remnants from the early 19th century when the island belonged to the Norwegian army. Lindøya, a little further into the fjord, is a car-free island with a limited number of summer cottages, all of which must not only conform to specific size regulations but can only be painted in one of three approved colours – red, green, or yellow. It is an idyllic island that does not cater to day trippers – public restrooms do not existent!

The island of Lindøya isn’t the only part of Norway that adhered to a limited colour palette; red, white, blue, green, or yellow appear to be the only paint choices available for purchase. Red is the predominant colour, and churches favour white – the following pictures are all from different villages!

In contrast to the white churches are the stave churches. This type of medieval wooden church was once the norm in north-western Europe. Now the only surviving examples outside of Norway are in Hedared, Sweden, and Karpacz, Poland (and that one was actually relocated from Norway to Poland in 1842). “Stave” refers to the vertical posts – staves – that support the structure.

Norway is one big hunk of granite cut through by hundreds of fjords, and is one “wow” moment after another. Traversing this stunning terrain poses something of a challenge, and the Norwegians have risen to the task. There are more than 100 car ferry connections (and even more passenger-only ones) and 900 road tunnels. Norway currently boasts the longest road tunnel in the world – Lærdal Tunnel (24.5 km / 15.2 miles) and the deepest subsea road tunnel – Ryfylke Tunnel (292 m / 958 ft below the surface and 14.4 km / 7 miles in length). We drove through both of these marvels of engineering.

Click on the video below to see one of the three road-stop caverns in the Lærdal Tunnel.

View this post on Instagram

Norway attempted to remain neutral in the immediate aftermath of Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September 1939. Neither Britain nor Germany felt that was an acceptable response. Both countries recognized the strategic value of placing bases along Norway’s coastline, and should the British gain control of the Norwegian shipping routes, Germany’s access to Swedish iron ore, a vital component in steel production, would be blocked. Germany didn’t hesitate to act. In April 1940, they invaded and, despite some Allied opposition, had control of the country in just under nine weeks.

It became the northern flank of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, a series of coastal fortifications stretching from Norway down through France. The massive Norwegian defensive works proved to be an effective deterrent – Allied forces made no attempt to invade the country after June 1940, much to the disappointment of the 400,000-odd German troops stationed there. The Kristiansand Kannonmuseum, on the site of the former Møvik Fortress, provided an interesting overview of Norway’s role during WWII, and showcases one of the largest remaining land-based guns in the world.

Runestones (in reference to the Germanic alphabet used in the inscriptions etched upon them) can be found scattered throughout Scandinavia, though the majority are in Sweden and Denmark. Their popularity peaked during the Viking Age, and coincided with the native population embracing Christianity. Some stones include only a runic inscription, while others incorporate elaborate designs along with the written message. I find them absolutely fascinating.

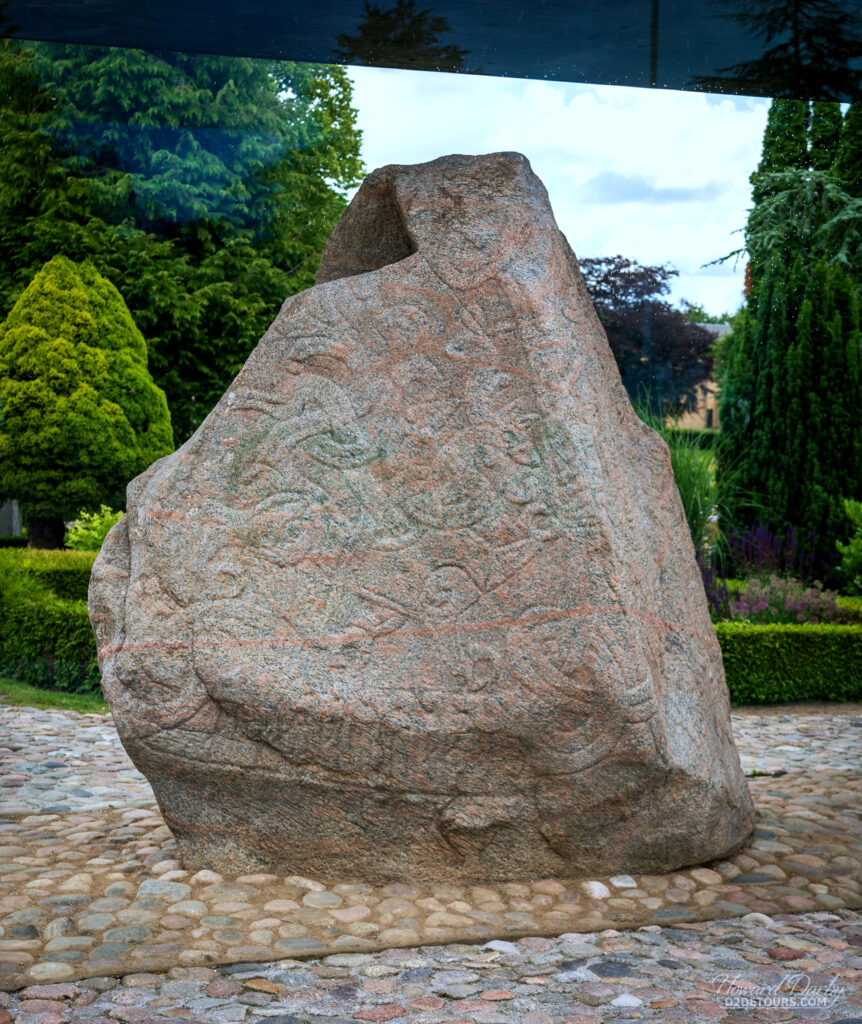

While these stones were primarily erected to commemorate the deceased, they are not headstones, but rather like a billboard on the side of the road extolling the virtues of a friend or family member. Many also document historic events. Two of the most significant Danish runestones are found near Jelling. Shortly before his death in 958, the Danish ruler Gorm the Old, erected a memorial stone for his wife, which reads: King Gorm made this memorial for his wife Thyrvé, Denmark’s adornment. This is the first time “Denmark” appears in written form. Gorm’s son Harald Bluetooth succeeded him to the throne.

Harald has quite the legacy. He united the Danish tribes into one kingdom under his rule and, in or around 965, converted to Christianity. To mark these achievements, he ordered a runestone be placed near his mother’s memorial. In addition to the inscription on his stone, which reads: King Harald raised this monument after Gorm, his father, and Thyrvé, his mother, Harald who won all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian, there is a depiction of Christ. All evidence points to this being the oldest Nordic representation of Christ and Danish passports feature it on their inside cover.

And if that legacy isn’t impressive enough, there’s Bluetooth technology. As noted on the Bluetooth website, this invention was so named because: “King Harald Bluetooth was famous for uniting Scandinavia just as we intended to unite the PC and cellular industries with a short-range wireless link.” The Bluetooth logo is the superimposed images of the runic symbols “H” (ᚼ) and “B” (ᛒ)!

In addition to the UNESCO app, we often look at Atlas Obscura for more unusual sightseeing opportunities (they have a website and phone app). Points of interest on that app do often also appear in more mainstream tourist guides, but invariably, there are some unique things we wouldn’t have found otherwise …

What better way to close this post than with a wall. The Danevirke (which literally means “earthworks of the Danes”) are a series of fortifications across the Jutland peninsula separating the North and Baltic Seas, with Denmark to the north and Germany to the south. While the Danevirke are now in Germany, historically this land belonged to the Danes, and these earthworks were designed to protect Scandinavia from southern invasion. The earliest earthen walls date from 650, with further expansion and reinforcement continuing through the 14th century. This 30 km / 19 mile barrier fulfilled its duty until 1864, when a series of wars with the Germans forced Denmark to cede this chunk of their territory.

Off on a cruise back to North America, and ultimately a visit to Calgary!