We left the sunny California desert and headed for the largest megacity in the world – Tokyo, population 37,274,000. February weather in Tokyo isn’t terrible, by Canadian standards. During our stay temperatures hovered around the 10° – 14°C (50° – 57°F) mark (we did have one day of snow with a high of only 0°C / 32°F) and actually thought the cooler temperatures made for pleasant walking conditions. Because we were a bit too early for sakura (cherry blossom) season, which occurs in late March to early April, there weren’t hordes of tourists so, all in all, we thought it was a great time to visit.

Like so many other massive metropolitan areas around the world, Tokyo began as a small settlement on the banks of a river. Edo, meaning “estuary,” was a fishing village on the uchi-umi (inner sea), a bay off the Pacific Ocean, and while it had existed for thousands of years a written record of it only first appeared in the 13th century Azuma Kagami, an incredibly detailed (almost like a diary) chronology of life in the region.

Edo’s evolution from fishing village to megacity really began in 1603 CE when the Tokugawa shogunate began its 250-year rule of Japan, a time in history known as the Edo Period. Quick bit of background … According to tradition, Japan was founded in 660 BCE by Emperor Jimmu. Emperors reigned over Japan until 1192 CE when the Kamakura shogunate effectively reduced the emperor to figurehead status. A shogunate is basically a military dictatorship (with a shogun at the helm) and between 1192 and 1868 was the form of government in Japan. Coincidentally, this is the timeframe during which feudalism became widespread in Japan with shoguns distributing land to loyalists (daimyo). Early in the 15th century, some of the largest land holding daimyo began to undermine the authority of the shogunate and over the next 150 years Japan was thrown into a state of near-constant civil war. The Tokugawa shogunate brought stability back to the country, in particular by regulating the daimyo through a strict set of laws and levies. Despite a rather draconian policy of isolation (nationals were forbidden from leaving the country, foreign literature was banned and foreign trade was severely restricted), Japan flourished during the Edo Period. As the de facto capital of the shogunate, the city of Edo experienced an economic and cultural boom swelling to a population of more than one million by 1720. Japan remained isolated from the rest of the world until well into the 19th century when the US decided enough was enough and it was time for Japan to open itself to the “benefits” of western culture. The Americans’ motives were not entirely altruistic. The US was already trading with China and the steam ships running these new trade routes required coaling stations; rumor had it there were vast coal deposits in Japan. Additionally, American whaling ships were pushing into the North Pacific and needed reliable supply stations. All of these factors made the geographic position of Japan very attractive. After a bit of bullying from the US, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States was signed in Edo on July 29, 1858.

The Tokugawa shogunate had been struggling for quite some time before the US came calling. Natural disasters, famine, corruption and incompetence were all putting a strain on the government and capitulating to the Americans was a bit like the straw that broke the camel’s back. In 1868, after 700 years of shogunate reign, the last shogun resigned and power was restored to the emperors. Emperor Meiji took his place as the 122nd emperor of Japan, moved his residence to Edo and formally changed the name of the city to Tokyo, which means eastern capital.

Dollars – We averaged just under $216/day Canadian ($161 USD / €151) for our 9 nights in Tokyo. We knew coming to Japan that our budget would be stretched, but were quite sure by spending most of 2023 in southeast Asia (Japan is technically considered east Asia), where the cost of living is much lower, we would easily be able to average out this extravagance over the balance of the year. And all things considered, I think we did quite well with our expenses in Tokyo, considering the nightly rate for our Airbnb was $149!

Environment – We were staying long enough in Tokyo that we wanted more than just a hotel room; we wanted a washing machine, kitchen facilities and somewhere comfortable to watch TV. We also decided that the Shinjuku Ward would be a good central location, even if that meant we were looking at places well outside our desired budget. The Airbnb we settled on at $149/night CAD (double what we normally would spend) was on the low end of the nightly-rate scale in Tokyo, but fortunately we were quite happy with the space. It was clean, had two-rooms (plus washroom) and was located in the Yotsuya neighbourhood with lots of restaurants, coffee shops, convenience stores and great access to subway stations. We were pleasantly surprised that despite the traffic noise (which was not insignificant as the windows were only single pane), it really just became white noise and never interfered with sleeping. And not to get too personal, but I think the single greatest invention ever might be the Japanese toilet and their heated seats.

Tips, Tricks & Transportation

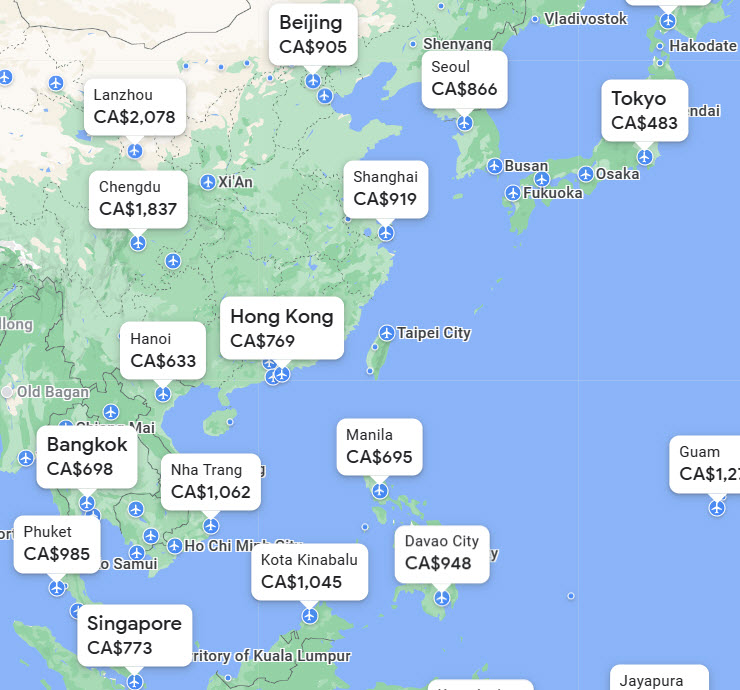

- Japan in February may not be everyone’s first choice, but the price of the flight was the determining factor for us. We planned to spend 2023 in southeast Asia and initially thought we would start in Vietnam. We use Google Flights when planning flights, in particular because of its wonderful mapping tool. Once you plug in your flight details (one way/roundtrip, starting point, date, class) you open their map and can see the prices for every flight departing from your selected airport to anywhere in the world. As we zoomed in on Asia, $483 CAD ($357 USD) popped up, one-way from LAX to Tokyo, which was significantly less than other destinations – so here we are!

- Google Maps is another amazing resource, and was incredibly helpful when navigating Tokyo’s rather intimidating subway system. Click on your end destination on the map (the map will automatically default to your current location as the starting point), then touch the “directions” button and finally select the icon for your desired mode of transportation (metro, walking, driving, etc). The detail page for the transportation method you chose will show the route options, the fare, the time the train/bus will arrive – and Japanese trains ALWAYS run on time! Once you pick your route and click “start,” that detail page will show the subway station platform (or bus number), whether the subway/bus is crowded, the number of stops on the route and the name of your final stop. If you’re taking the subway it will even suggest which car to use for optimal exiting at the final stop.

- There is always English signage in the subway/train stations, so in combination with the Google Maps instructions, it was pretty easy to find our way around. We tried to steer clear of the subways during rush-hour to avoid the crush of people that often require train attendants to push as many people on to the cars as possible. We saw what we figured were likely the white-gloved oshiya (train pushers) on the platforms a couple of time, but their services weren’t ever required – thankfully.

- We thought the easiest way to pay for public transportation in Japan was by using one of the “IC” cards. In Tokyo we picked up a Suica card. Every region has its own name for the IC card (Suica is the Tokyo version) but regardless of what the IC card is called, it works in every city. These cards can be used on subways, buses, or trains anywhere in Japan, except for the Shinkansen (high-speed bullet train) travelling between the major centers (like Tokyo to Kyoto). We opted to get the Welcome Suica card which is designed for tourists and does not require a deposit to use the card. This card can be purchased at the “Welcome Suica” machines in the Tokyo airports, as well as a few major train stations, and is only valid for 28 days – we’re in Japan for 26 days so that worked for us. One disadvantage to the Welcome Suica card is that any unused funds left on the card are not refundable. If you purchase a regular Suica card you will be eligible for a refund of unused funds, but the refund booths are only located in Tokyo. All versions of the cards are reloadable and we figure we won’t be left with a balance on our cards as in addition to public transportation, the IC cards can be used at convenience stores and some restaurants – even as a partial payment to clear the remaining balance, covering the difference with cash.

- There are ticket machines to buy Shinkansen (bullet train) tickets right in the train stations as well as some apps to book online, but we recommend you get your ticket(s) from an actual human. We used the machine and obviously missed a step because when we tried to pass through the gate to the trains we were stopped and told we needed TWO tickets. Fortunately we’d allowed ourselves a bit of extra time to get to the train platform (because Japanese trains are NEVER late) and there was a ticket booth with live agents right near the gate, enabling us to quickly rectify our mistake.

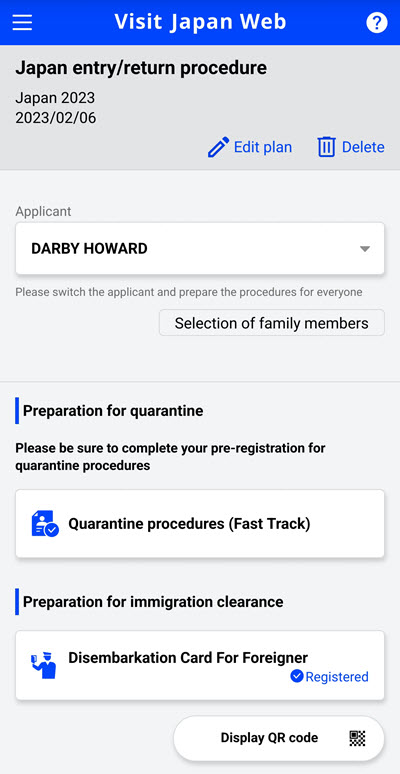

- To enter Japan you will need to use the Visit Japan Web site to complete an online form, including COVID vaccine details and customs and immigration information. You’ll then receive a QR code on your phone that you will be asked to present at various points as you walk through the airport. There was a gaggle of people in pink vests stopping disembarking passengers to confirm you had completed the COVID check-in on the app and would help you if necessary (I love the organization of this country!). You will need to be on wifi at the airport (or activate your data package) to use the app, so just in case there were any technology glitches we made sure to save a screen capture of the QR codes on each of our phones.

- Japan is a NO TIPPING culture (HOORAY). In fact it’s considered a bit of an insult to imply that an employee wouldn’t do a good job without the incentive of extra pay – one less thing to worry about when calculating exchange rates on restaurant bills and cab rides! If you do leave extra money on the table in a restaurant don’t be surprised if someone comes running after you to return the money thinking you accidentally left it on the table.

- Be aware that finding a trash can on the streets of Tokyo, and much of Japan, is practically impossible, they simply do not exist. So you may want to keep a small bag in your pocket to carry any trash you might accumulate during the day and then dispose of it back in your residence.

- The sidewalks in Tokyo (and train stations) have yellow tiles running down the middle of walkways. They have different textures/patterns (straight lines/bumps) and are designed for the visually impaired to guide them and identify where sidewalks intersect or there is a traffic crosswalk.

- Surprising to us North Americans, 7-Elevens are the recommended place to use ATMs. As an added bonus they (and many of the convenience stores) sell some decent pre-prepared meals – again something completely shocking to a North American. The Lawson chain of stores have a huge selection of pre-packaged pastries that were replenished on a daily basis and we kept those on hand for a quick breakfast before a day of wandering.

- The Japanese people are extraordinarily kind. Even if they don’t understand English they will do whatever they can to help you – even if you haven’t asked and just look perplexed! We had a number of those occasions including a bus driver who used the external speaker on his bus to call out instructions to us when we clearly didn’t understand why the bus we were waiting for bypassed us (we had to run down a quarter block to the next stop) – amazing.

Out and About – The metropolitan area of the Tokyo Prefecture stretches for 25 kilometres (15 miles) north/south, and 90 kilometres (56 miles) east/west, roughly 2,187 square kilometres (844 sq. miles), and is composed of numerous administrative wards, cities, towns and districts.

Shinjuku – In the shadow of modern high-rise buildings are six narrow alleyways jam-packed with a hodgepodge of narrow, two-story adjoining buildings. Unlike the surrounding area, which was redeveloped during Japan’s economic boom following WWII, the Golden Gai (Golden Block) has remained relatively unchanged since the late 1950s, early 60s when it was known as a red-light district. Today nearly 200 bars and eateries inhabit the buildings. It feels virtually empty during the day, coming alive after 8pm. The establishments are teeny, tiny, some with room for no more than 5 or 6 patrons, and don’t be surprised to see a few signs saying “no foreigners/tourists” or “regulars only.” Be aware, these alleys are considered private property and inappropriate conduct on the streets will not be tolerated, which, not surprisingly, includes smoking, loitering, shouting, singing, drug use or alcohol consumption, but photography is also prohibited unless you first seek permission. We first strolled through the area in the middle of the day when no one was about, and didn’t see the sign for forbidden activity until we were leaving and already snapped a few pictures – oops!

The Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden was originally the residential garden of an Edo daimyo (roughly 1772 CE), and has undergone several incarnations over the years: experimental agricultural center, botanical garden, and imperial gardens. Air raids during 1945 destroyed most of it, but it was soon rebuilt and opened to the public as a national park in 1949. The garden has a circumference of 3.5 km and features three styles: French Formal, English Landscape, and Japanese Traditional. It is open year-round with flora varying according to the seasons. In February, several varieties of flowers were blooming – Japanese apricot trees, camelia, amur adonis, paper white narcissus, and a couple of kanzakura (flowering cherry) trees, that must be situated such that they receive enough sunlight to bloom early; the actual “Cherry Tree” area must be spectacular in the spring! The “Avenue of London Plane Trees” is probably quite pretty in the summer when the trees are in leaf, but I rather liked the barren winter version. Entry to the garden is ¥500/pp ($5.11 CAD / $3.80 US / €3.54).

On a couple of occasions we were thwarted in our efforts to sight-see by building closures – the Shinjuku Historical Museum is closed on the 2nd and 4th Mondays of each month, and the observation deck in the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building is closed on the 1st and 3rd Tuesdays! Fortunately our schedule allowed us to go back to the observation deck, which is free, and experience a spectacular 360° birds-eye view of the city.

A lot of our time in Tokyo was spent hopping on the subway, taking a train out to one of the various municipalities and then just wandering the streets, often timing our visit to coincide with sundown so Howard could do some nighttime photography.

Shibuya is a trendy shopping district with a very youthful vibe. I did not feel hip and cool walking those streets, but it was fun to witness the “Shibuya Scramble.” The lights at the intersection located in front of the Shibuya Station Hachikō exit stop traffic in all directions, allowing pedestrians from every corner to scramble across the street. The heaving mass of humanity depicted on social media isn’t really there in the middle of the day, but we definitely got a sense of what it must be like during rush-hour, and I think it’s always fun to see iconic landmarks.

Stalls full of knickknacks and nibbles line the Nakamise-dori Street, in Taito City/Asakusa with the Kaminarimon (Thunder) Gate of the Sensō-ji temple beckoning tourists to come closer.

The Sensō-ji temple, dedicated to Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy, is considered to be the oldest temple in Tokyo, dating from 645 CE, although disasters both natural (earthquakes) and man-made (1945 firebombing of Tokyo) have necessitated numerous rebuilds. The rebuilding project undertaken between 1951 and 1958 was an important symbol of Tokyo’s rebirth following WWII. Just slightly to the southwest of the temple is a Gojunoto (five-storied pagoda) that was first built in 942 CE, destroyed completely in the 1945 bombing and rebuilt in 1973. Pagodas typically have very little interior space, instead serving as a ceremonial space for sacred relics. On the topmost storey of this particular pagoda is a relic of the Buddha’s ashes, donated in 1966 by the Isurumuniya Temple in Sri Lanka.

Taito City is the home of traditional Edo culture and the Edo Taito Traditional Crafts Museum has an extensive display of handicrafts and their history. It’s free of charge and the docent was more than happy to chat with us and answer all of our questions.

Minato City – In 1858, soon after Japan re-opened its borders to the western world, Japan and France signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce which marked the beginning of a long friendship between the two countries. In tribute to their relationship, in 1998 one of the replicas of the Statue of Liberty, namely the one from Île aux Cygnes in Paris, was temporarily displayed in the Odaiba Seaside Park in Tokyo Bay. The exhibit proved to be so popular that when the statue was returned to France in 1999 a replica was erected (with French approval). At only one-seventh the size of the New York version, it’s still quite captivating at night with the solar powered lights on the Rainbow Bridge illuminating the background.

Koto City – Everyone’s definition of art is different. In front of the Diver City Plaza is a full-scale Unicorn Gundam, a robot from a popular novel series. At certain times during the day it will transform from unicorn mode to destroy mode – much to our disappointment at night it just stands there quietly, but at least it was brightly lit.

The Akihabara district is known for manga/anime and video gaming stores. If I felt old in Shibuya, I felt downright ancient walking around Akihabara. Every Sunday between 1pm and 6pm (5pm from October through March), the Chuo Dori (main street) is closed to vehicle traffic making it a popular spot for an afternoon walk.

Kawagoe City, in the Saitama Prefecture, is about a 45 minute train ride from the Shinjuku station in Tokyo. It is sometimes referred to as little Edo as many of the streets still contain the traditional architecture from the 1800s.

The original “Toki no Kane” (bell tower) was built over 400 years ago but what stands today is from 1894. One year after the Great Fire of Kawagoe destroyed nearly a third of the city, the shop merchants immediately saw to the reconstruction of the bell tower, even before rebuilding their own shops, as the ability to tell time was essential in conducting business. The bell is rung daily at 6am, noon, 3pm and 6pm.

Kashiya Yokocho is a sweet street, lined with shops selling penny candy, souvenirs and other treats. If sponge toffee and cotton candy had a baby it might be the 95 cm (3ft) long baguette called fugashi – dried wheat gluten coated in brown sugar. It truly looks like a baguette and lots of school children had them in their hands or poking out of backpacks so we thought maybe it was something you picked up for dinner on your way home from school. Our first clue should have been that it was sold in “candy alley.” Sweet is an understatement and apparently one of the popular ways of serving it is to fry slices in butter – OMG!

The green Starbucks logo is ubiquitous in Tokyo; shops are frequently within mere blocks of each other and so I found it quite amusing that in Kawagoe they have tried to blend into the background.

We enjoyed the train ride out to Kawagoe. The highrises of Tokyo give way to shorter and smaller multiplexes, and what I found particularly interesting was the complete lack of graffiti along the tracks.

Us (our thoughts on the area) – Howard had been to Japan about nine years ago when he and a fellow shooter were invited by one of the local Fast Draw clubs to come compete in the Japan championships. He was captivated by the culture, and we had originally planned for Japan to be our first nomadic destination. That didn’t quite work out, but we are here now and I can completely understand why he developed such an affinity for this fascinating part of the world. We enjoyed everything about Tokyo, the vibe, the food, the people, and I can’t wait to experience more – off to Kyoto!

Restaurants – We are not fans of sushi. Happily, despite Japan being considered the sushi capital of the world, there are sooooo many other options available in Tokyo – just walking the streets the air is full of enticing aromas.

We tried shabu shabu and sukiyaki at Nabezo, which has several locations in Tokyo. As complete novices to this type of eating, Nabezo was a good choice as they provided an English instruction sheet. Notwithstanding the instruction sheet, our delightful waiter, who didn’t speak a lick of English, demonstrated the technique, complete with sound effects.

Shabu shabu and Sukiyaki are similar in that both consist of thinly sliced meat (we chose beef and pork) and bite-sized vegetables cooked in a hot pot, very similar to fondue, which are dipped in various sauces after cooking. Shabu shabu translates to “swish swish” in reference to the food gently swishing in a seasoned broth. As the beef is parboiled, the fat dissolves into a rather unappetizing scum floating on the broth but each table is supplied with strainers and water to whisk the foam away and supposedly the final product is “fat-free.” Pork is usually the choice of meat for sukiyaki which is then simmered in a thick salty-sweet sauce along with noodles and vegetables. The vegetables and/or noodles provide a base in the sauce with the meat laid atop, flipping it once to ensure it is thoroughly cooked. Once fully cooked the meat, veg and noodles are dipped in a dish of raw, scrambled egg and immediately consumed – raw egg sounds a mite yucky, but was delicious. The whole meal was delicious and filling. It’s an all-you-can-eat in 100 minutes experience which was ¥3000/pp plus tax. Our meal came to ¥7040 ($72 CAD) and although alcoholic beverages and soft drinks were available, we just drank water.

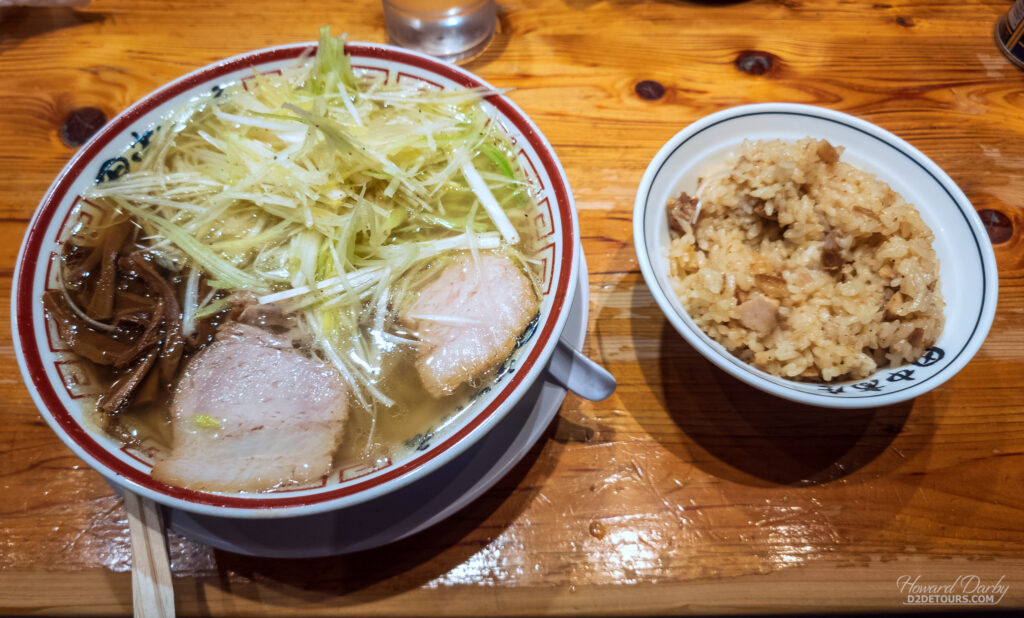

Of course we also tried ramen. Every region in Japan has its own variation of ramen, but generally it consists of wheat noodles served in broth, topped with sliced pork, nori (dried seaweed), menma (bamboo shoots) and scallions.

It’s a quick, inexpensive dish that is probably not the best choice if you’re watching your sodium intake, although if you avoid tonkotsu (pork broth) and stick with soy or miso-broth ramen you can feel like you’ve made a “healthy” choice. Most of the restaurants are compact affairs and you don’t “dine” – slurp up your noodles (which is perfectly acceptable, and in fact encouraged) and get out because there are likely people lined up outside waiting to get in. Ordering your bowl is a bit of an experience. Vending machines are located outside the shops. Make your choice, pay with either cash or your Suica card, get your chit, and hand it to the hostess, if there is one, or directly to the cook, find a seat and enjoy! The vending machines may or may not be in English, and often don’t have a picture of what you’re ordering either, so Howard had done a little research ahead of time. He used Google Lens to translate the wording on the restaurant’s Google Maps page, and knew which dishes we should order. We also may have looked somewhat confused because the hostess quickly popped outside to offer us assistance!

Speech – Not everyone speaks English, nor does all of the signage include an English translation, but we found that anything you need to be aware of as a tourist was clearly indicated in English. And a significant number of people did have some grasp of English, which when combined with a few pantomimes meant we had no trouble communicating. Plus we found the Japanese people exceptionally kind and they all seemed to genuinely want to help us.

- Konnichiwa (kōn-ni-chi-wa) – Good afternoon (technically should only be used up until about 5pm);

- Konbanwa (kōn-ban-wa) – Good evening;

- Mata ne (mah-tah-neh) – literally “See ya” (saying goodbye is rather confusing and very dependent on the situation. Sayounara definitely shouldn’t be used; it has a sense of finality to it, like you will never see the person again. Mata ne seemed like the best compromise for tourists);

- Kudasai (koo-da-sigh) – Please;

- Arigatou (ah-re-gah-toh) – Thank you;

- Arigatou gozaimasu (ah-ree-gah-toh goh-zah-ee-mahs) – Thank you very much;

- Hai (hi) – yes (the Japanese are uncomfortable with a harsh “No” and try to avoid using it in conversation);

- Wakarimasen (Wa-ka-ri-ma-sen) – I don’t understand;

- Eigo o hanase masu ka (E-i-go o ha-na-se mahs kah)? – Can you speak English;

- Tetsudatte kuremasen ka (tets-u-det kur-e-mah-sehn kah? – Could you help me;

- Sumimasen (soo-mee-mah-sehn) – Excuse me;

- Gomen nasai (go-men na-sai) – I am sorry.

I absolutely loved this edition!! Fascinating and informative. I don’t see myself even going to Japan (but never say never) so I really appreciated all the details you shared and the numerous wonderful photos. Very glad you got to join Howard on this trip, Whitney! 😉

Pingback: Our Top 10 Destinations for Long Stays - D2 Detours